1 Introduction

The nationwide three-digit number 988 went live on July 16, 2022—a landmark moment and long-awaited opportunity for parity that could help put crisis response for mental health, substance use, and suicidal emergencies on par with physical ones. That is, if 988 contact centers connect to a comprehensive crisis system and 911 diverts behavioral health calls to 988 (1). However, child and adolescent mental health experts have long argued that existing crisis systems have been built for adults, not young people. According to Dr. Jeff Bostic, medical director of the MedStar Georgetown Center for Wellbeing in School Environments, existing mental health care focuses on people ages 18 to 65. “Next in line is 65-plus,” he said, “and last on the list are kids.”

As the United States reels from the COVID pandemic, it is also experiencing twin mental health and substance use epidemics. Both predated but were exacerbated by the disaster, and children and adolescents have been particularly affected. In the fall of 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collected data from more than 17,000 high school students at 152 public and private schools for its Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). The survey revealed that 42 percent of participating students experienced “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness” in the past year—a 5 percent increase from pre-pandemic times. In addition, more than 20 percent seriously considered suicide, and 10 percent reported a suicide attempt.

Overdose deaths in the United States jumped by 30 percent between 2019 and 2020 and 14.9 percent in 2021, with deaths from synthetic opioids, psychostimulants, and cocaine continuing to climb. Young people ages 15 to 24 had the second lowest overdose death rates in 2019 and 2020; however, they experienced a 49 percent increase in 2020, the largest of any age group. According to the fall 2021 YRBS survey of U.S. high schoolers, while substance use has decreased overall, there is disproportionate use among historically marginalized populations. For example, alcohol use was highest among American Indian or Alaska Native and female high school students, and LGBQT+ high schoolers were more likely than their peers to misuse prescription opioids.

In October 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics and several other child health focused organizations declared a national child and adolescent mental health emergency.

Despite the return to in-person school, pediatric mental health challenges continue to rise, and behavioral health service use has yet to rebound. This paper examines data from the CDC, the McKinsey Health Institute, YouthLine at Lines for Life, the Trevor Project, 988 Lifeline, the Institute of Education Sciences’ National Center for Educational Statistics, and other youth-focused organizations to give a snapshot of what young people are experiencing, exploring innovations that help mitigate crises for children and adolescents and divert them from a law enforcement response and the emergency department.

2 Youth Mental Health Challenges

According to Emily Moser, director of YouthLine Programs at Lines for Life in Oregon (2), the pandemic supercharged the challenges of navigating early adolescence. COVID added barriers to face-to-face peer connection during a time flush with developmental changes. YouthLine is a nationwide peer-to-peer support helpline that young people ages 11 to 24 can access by chat, email, and text. Trained peer volunteers are between 15 and 20 years old.

During the first year of the pandemic, the number of middle school callers (ages 11 to 14) grew. In 2020, they made up 20 percent of young people contacting YouthLine. These ages were also among the group (ages 0 to 14) that McKinsey Health Institute identified as having the largest decrease in behavioral health service use in 2020 (3).

YouthLine is a nationwide peer-to-peer support helpline that young people ages 11 to 24 can access by chat, email, and text.

“The preteen and middle school years are a time of exploration and branching out in a socially sensitive way,” said Moser. “They’re asking, ‘Who am I?’ ‘Who are my friends?’ Who are my people?’”

Cooper Yacks was an eighth-grader at The County School in Maryland when COVID hit the U.S. Initially excited about virtual school, he soon realized he missed the socialization of being in person. While he could see his friends on Google Meet, Cooper said it wasn’t the same—he couldn’t whisper jokes to them or see them between classes. “I’d taken social interactions with my friends for granted,” he said. “I couldn’t do anything. I felt isolated.”

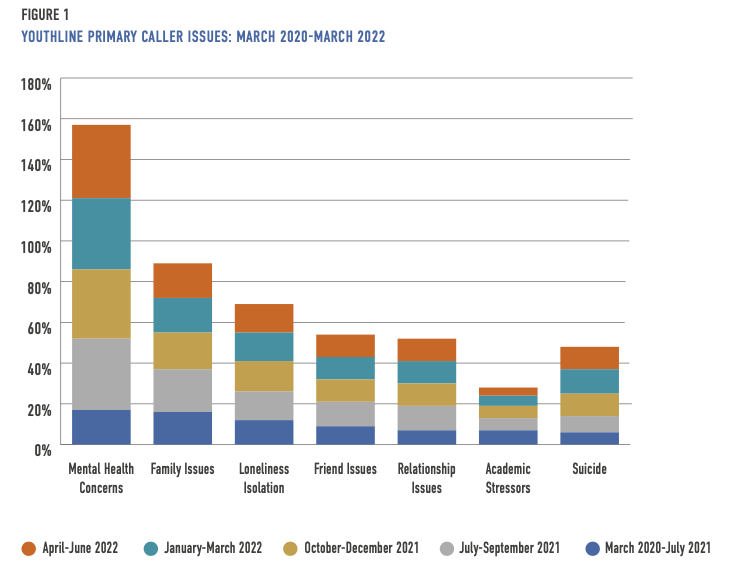

Today, 72 percent of those reaching out to YouthLine are between 13 and 24 years old. Only 7 percent are younger than 13. The remainder comprises parents, teachers, and other adults (4). While the topics young people reach out about—mental health issues; family, friend, and relationship issues; suicidal thoughts; and loneliness and isolation—have mostly remained consistent throughout the pandemic, there are noteworthy shifts. For example, the percentage of youth contacting the line about mental health concerns has more than doubled from 17 percent (March 2020 – January 2021) to 35 percent (July – September 2021), where it has hovered, give or take a percentage, ever since (5).

In the first year and four months of the pandemic, academic stressors were among the top six reasons young people contacted YouthLine. But, since July 2021, the concern has been surpassed by suicide, with youth contacting the peer-to-peer line to discuss suicide roughly doubling from 6 percent ( March 2023-January 2021) to 11-12 percent (October 2021 – June 2022), where it has remained. In addition, despite the return to in-person school across the U.S., loneliness and isolation has increased slightly since July 2021, from 12 percent (March 2020 – January 2021) to around 14-15 percent (July 2021 – June 2022).

While many young people have faced mental health challenges during the pandemic, marginalized populations have been at increased risk.

The COVID experiences for children and adolescents have not been monolithic. Not only did U.S. communities ebb in and out of viral surges, but state and local leaders also differed in their response to the virus. While many young people have faced mental health challenges during the pandemic, marginalized populations have been at increased risk. The previously mentioned CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) also revealed that LGBQ+ and female high school students are experiencing extremely high levels of sexual violence. In 2021, 22 percent of LGBQ+ and 18 percent of female students experienced sexual violence, with 20 percent and 14 percent, respectively, reporting they had been raped at some point in their young lives. American Indian or Alaska Native and multiracial high school students have also experienced a disproportionate risk of sexual violence, with 18 percent and 12 percent having been raped compared to 8 percent of white high schoolers. According to a longitudinal study published in The Lancet, sexual violence in mid-adolescence contributes considerably to mental health challenges, including self-harm and attempted suicide.

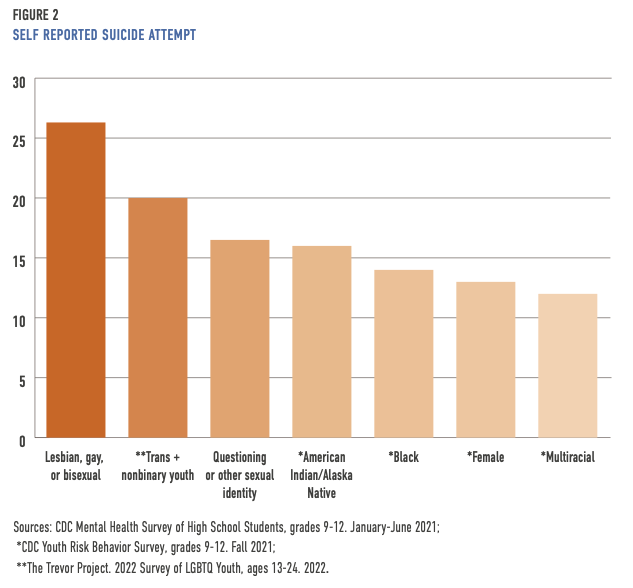

A one-time CDC survey on U.S. high schoolers’ mental health, suicidality, and connectedness—which collected data from 7,705 U.S. high schoolers between January and June 2021—revealed the highest rates of attempted suicide to be among gay, lesbian, or bisexual, questioning or other (sexual identity), American Indian or Alaska Native, Black, female, and multiracial high school students. Months later, the fall 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), which included more than 17,000 high school students, revealed a few notable differences, including a higher percentage of Black high schoolers who self-reported a suicide attempt. The survey also highlighted that Black high schoolers were less likely to report poor mental health or persistent sadness or hopelessness compared to most races and ethnicities; however, they were more likely than Asian, Hispanic, multiracial, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and white students to report having made a suicide attempt.

In May, the Trevor Project released its 2022 national survey on LGBTQ youth mental health, which included almost 34,000 young people ages 13 to 24. The survey revealed that 45 percent of participants seriously considered attempting suicide, and nearly 20 percent of transgender and nonbinary participants attempted suicide in the past year. According to Dr. Myeshia Price, the nonprofit’s director of Research Science, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning youth face specific minority stressors like discrimination, stigma, and victimization. “They’re already experiencing the stress of being an adolescent, a young person,” she said. “Then you add LGBTQ-specific stressors like discrimination and being victimized.”

Separating youth from in-person school has had layered adverse effects, and many young people lost in-person peer connection and support that go hand-in-hand with school. Kevin, a ninth grader in New Orleans who is transgender, shared this was especially challenging for LGBTQ adolescents. He highlighted that school is where LGBTQ youth see their friends and in-person support and student-run youth organizations like Genders and Sexualities Alliance (GSA) clubs are held. “One of the most important things is hearing from other people like you who have gone through and are continuing to go through the same experiences,” he said. “We not only felt disconnected from school but also the support we have there, like GSA clubs.”

Kevin pointed out that to address LGBTQ youth mental health, communities must connect schools and mental health services. “Mental health services help destigmatize mental health challenges,” he said. “Education and mental health go hand-in-hand—you can do well in school and be okay.” Unfortunately, behavioral health service use has not rebounded for most communities, even with the return to in-person school. One reason, as Kevin mentioned, is poor connectivity between schools and mental health services. Another is the ongoing challenges from the pandemic, like chronic student and teacher absences and a nationwide substitute teacher shortage.

Mental health services help destigmatize mental health challenges… Education and mental health go hand-in-hand—you can do well in school and be okay.

3 Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health Service Use

Since COVID began, outpatient behavioral health service use among children and adolescents has decreased. To measure the impact of the pandemic on utilization, McKinsey Health Institute analyzed claims data from 250,000 providers who delivered behavioral health care to more than 35 million Americans in 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022—including those enrolled in commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare plans (6). Claims for outpatient behavioral health services decreased in 2020 and have not fully rebounded or grown except in psychotherapy and evaluation and management (E&M) for ages 19 and over. However, in February and March 2022, service use for both also increased for adolescents ages 15 to 18 (7). Evaluation and management can occur in any setting, including inpatient and the emergency department, but is most typically delivered in a primary care office. For this analysis, an E&M claim requires a primary diagnosis of a behavioral health condition on the same claim. For example, a child meets with their pediatrician, and the primary reason for the visit is generalized anxiety disorder.

It is important to note that along with the pandemic came rapid regulatory and policy changes removing service delivery barriers for telehealth. According to McKinsey data, the largest jump in tele-behavioral health visits occurred among youth, with a peak proportion of 46.7 percent of all behavioral health services delivered virtually in May 2020 (versus roughly 1 percent pre-pandemic). That same month was also when children and adolescents experienced a considerable dip in outpatient behavioral health service use.

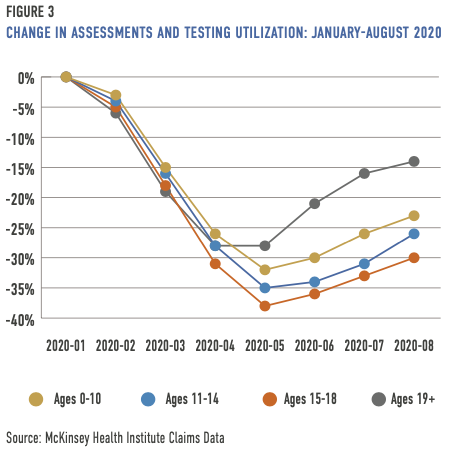

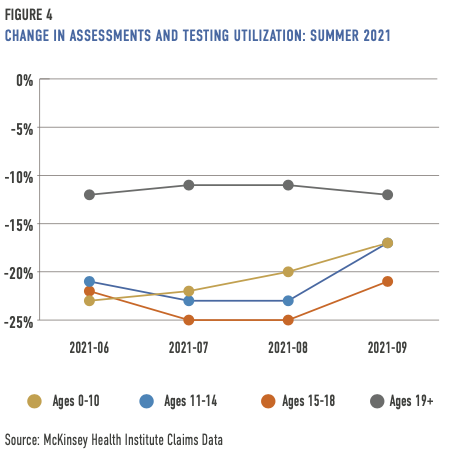

Claims data throughout the pandemic illustrate age and gender disparities in behavioral health outpatient service use. While assessments and testing haven’t returned to pre-pandemic levels for any age group, young people have experienced the largest decreases.

From April through August 2020, compared to 2019, psychiatric diagnostic evaluations, brief emotional and behavioral assessments, and annual mental health screenings dropped between -30 percent and -38 percent for teens ages 15 to 18. The average for those months was -31 percent for children and adolescents ages 0 to 18 compared to -21 percent for ages 19 and over. Decreases also correlated with long school breaks during the summer and winter months. Assessment and testing have rebounded least for children ages 0 to 10.

Schools are often a primary referral source for behavioral health services, and the shift for many communities to remote learning created barriers to identifying students in need. In May 2021, Kevin Collins, data lead for McKinsey Health Institute, shared that “…with children away from in-person school and corresponding support networks, there are fewer opportunities to identify their needs.” In June 2021, nearly 30 percent of public schools still had hybrid learning—a mix of virtual and in-person school (8).

While assessments and testing haven’t returned to pre-pandemic levels for any age group, young people have experienced the largest decreases.

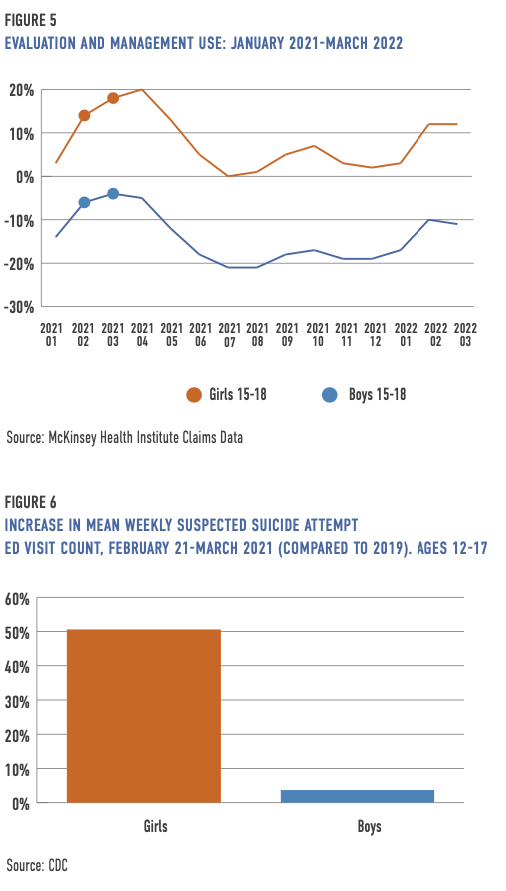

The claims data illustrates a greater rebound in outpatient behavioral health service use among girls than boys for all behavioral health areas (assessment and testing, psychotherapy, and evaluation and management—most often provided in a primary care office but also in inpatient and emergency department settings). According to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data collected in the fall of 2021, 41 percent of teen girls reported poor mental health compared to 18 percent of teen boys. Suicide attempts were also disparate, with 13 percent of girls reporting they have attempted suicide compared to 7 percent of boys.

The CDC reported that in 2020 the proportion of emergency department visits for mental health concerns rose 31 percent compared to the rate in 2019. By early May 2020, emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts increased for ages 12 to 17—the mean weekly number was 22.3 percent higher during the winter of 2021 than in the same timeframe in 2019. However, increases were higher for girls than boys. For example, between February 2021 and March 2021, the mean weekly ED visits count for suspected suicide attempts was 50.6 percent higher for girls (compared to the same period in 2019), while boys experienced a 3.7 percent increase (9).

Despite the return to in-person school (schools are a primary referral source to mental health services), outpatient behavioral health service use has yet to experience a complete rebound. According to the Institute of Education Sciences’ National Center for Educational Statistics (IES is the evaluation, research, and statistics arms of the U.S. Department of Education), public schools participating in the center’s School Pulse Panel survey have reported that the pandemic harmed student socio-emotional and behavioral development, 87 percent and 84 percent respectively, during the 2021-2022 school year (10). Although the need for mental health services appears to be on the rise, school disruption from intermittent COVID-related closures and student and teacher absenteeism has created additional barriers to identification and referral. Absenteeism is not always a result of the virus itself. During the pandemic, families have experienced personal and financial hardship, which has also affected attendance. For example, researchers found that decreases in third-grade test scores for the 2020-2021 school year on Ohio’s English language arts assessment were tied to COVID-affected unemployment, which decline most pronounced in areas hardest hit by unemployment.

According to the School Pulse Panel survey, during the 2021-2022 school year, 72 percent of participating public schools reported chronic student absenteeism—missing at least 10 percent of the school year—compared to pre-COVID. Compared to the 2020-2021 academic year, 39 percent of participating public schools reported increased chronic student absenteeism. Public schools reported similar percentages for teacher absences in the 2021-2022 school year—a 72 percent increase compared to a pre-COVID school year and 49 percent compared to the 2020-2021 academic year. There has also been a substitute teacher shortage, which means administrators, teachers on their prep period, and even non-teaching staff have had to cover classes.

4 The Emergency Department Default

When services for children and adolescents do not exist or are insufficient or inaccessible, the default responders are often law enforcement, and the default providers are the emergency department. Emergency department (ED) use highlights gaps in the health care system; this is especially true during times of disaster like the COVID pandemic. In a commentary published in the NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, physicians called ED crowding the “canary in the health care system.” As with the unwell canary in the coal mine, the authors wrote that ED crowding is a “symptom of health care system dysfunction.”

Dr. Benjamin Druss, a professor and Rosalynn Carter chair in mental health at Emory University’s School of Public Health, called the pandemic a “…huge stress test, showing us how we use emergency rooms, both for medical and mental health care.” According to an article published in Pediatrics in 2019, between 2011 and 2015, the number of young people—ages 6 to 24—going to the emergency department for psychiatric visits increased by 28 percent. The increase was even starker for children ages 5 to 17 years old, with emergency department visits for mental health disorders among this age group rising by 60 percent between 2007 and 2016. In that timeframe, there were also higher spikes for deliberate self-harm and substance use disorders, 329 percent and 159 percent, respectively (11).

During the early portion of the pandemic—between January 1 and October 17, 2020—the proportion of mental health related ED visits rose among children ages 5 to 11 (24 percent increase) and 12 to 17 (31 percent increase).

During the early portion of the pandemic—between January 1 and October 17, 2020—the proportion of mental health related ED visits rose among children ages 5 to 11 (24 percent increase) and 12 to 17 (31 percent increase) (12).

Reina Chiang, a 15-year-old living in Montgomery County, Maryland, when COVID hit, was among them. She felt alone for months before the pandemic, her thoughts of suicide growing little by little. By Spring 2020—when Maryland was on lockdown—she said there was “nothing to do but sit at home and think.” For Chiang, now a college student, the emergency department is synonymous with “a lot of sitting around” that has ranged from hours to three days. Her mother, Kana Enomoto, is the director of Brain Health at the McKinsey Health Institute and former acting administrator at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). She said witnessing her daughter’s experience “was heartbreaking” and also showed her “how much has to change.”

Although most communities did not have sufficient behavioral health services for children and adolescents even before COVID, social distancing requirements to halt the spread of the virus meant in-person services and supports were less accessible or unavailable. The nation is also experiencing a preexisting shortage of pediatric psychiatrists. Consequently, when a youth is in crisis, there is often nowhere else for them to go but the emergency department. Dr. John Santopietro, physician-in-chief at Behavioral Health Network and senior vice president at Hartford HealthCare, has said the emergency department is the most common entry point into the U.S. mental health system for children and their families.

When there is insufficient behavioral health crisis care accessibility, children and adolescents can languish in the emergency department for hours, days, and sometimes months. The time someone spends in the emergency department waiting for care, often for a bed in inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, is called psychiatric boarding. According to a study published in JAMA in November 2021, nearly all participating pediatric practitioners (98.9 percent) at 88 hospitals reported their hospital regularly boards children and adolescents waiting on inpatient psychiatric care. While there is a shortage of pediatric psychiatrists, the lack of interconnectivity in health care, even within the same hospital system, plays a significant role. For example, in 2018, at the University of Vermont Medical Center emergency department, roughly 73 children spent, on average, 3.5 days awaiting psychiatric care. Even though 11 full-time pediatric psychiatrists worked on the hospital campus nearby, they rarely interacted with kids experiencing behavioral health care challenges in the ED.

One state over, concerned about the increasing number of people waiting for admission at the state hospital, NAMI New Hampshire developed a dashboard that has tracked wait times since 2017. The day with the highest number of children (51) waiting for a bed occurred on February 14, 2021. (Before the pandemic, the peak for children waiting was

27 on May 18, 2017.) There were also spikes in October 2020 and other days in February 2021.

For example, the odds of psychiatric boarding increased for Black children, children ages 10 to 13, those experiencing suicidal or homicidal ideation, and children whose emergency department visit fell on a weekend or holiday.

Historically, the discussion on pediatric psychiatric boarding has centered on a lack of inpatient beds for children and adolescents. However, a 2003 study published in Pediatrics revealed the calculus to be more nuanced than whether a bed is available. For example, the odds of psychiatric boarding increased for Black children, children ages 10 to 13, those experiencing suicidal or homicidal ideation, and children whose emergency department visit fell on a weekend or holiday. Youth with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities can also face exceptionally long wait times. For example, according to the Washington Post, Howard County General Hospital’s emergency department boarded 18-year-old Zach Chafos for a total of 76 days (a stint of 28 days and then later 48 days) in the fall of 2020 and spring of 2021. They were waiting for a psychiatric bed to become available. Tragically, he died from an epileptic seizure 10 days into his psychiatric hospital stay.

In December 2016, the U.S. Congress passed the 21st Century Cures Act, allowing SAMHSA to fund state development of real-time psychiatric bed registries. According to Ted Lutterman, senior director of government and commercial research at the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute (NRI), many states are using the funding to go beyond just tracking psychiatric beds and developing real-time comprehensive crisis services registries. He said having a real-time database that connects people to the level of care they need along the entire continuum of behavioral health care services, including outpatient appointments, is critical. “When a registry only focuses on beds, that’s likely where people will end up,” he said. Jeff Richardson, COO of Sheppard Pratt Health System’s community-based behavioral health programs, echoed these sentiments. He told the Washington Post that bed registries are only part of the solution. “There will never be enough beds, especially if we have nowhere to put these patients afterward,” he said. “We have to invest in a better community-based system of care.”

5 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline and Youth Lines

As of July 16, 2022, there is a three-digit number for mental health, substance use, and suicidal crises for all Americans, including children and adolescents. Former FCC Chair Ajit Pai has said the nationwide number effectively establishes “988” as the “911” for mental health emergencies. People can call or text 988 or use the online chat to reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (formerly the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and commonly called “988 Lifeline”). In November 2021, the FCC expanded 988 to include texting. FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel said in a statement that adding text would expand people’s access to 988 Lifeline, especially for young people and those more comfortable or who feel safer reaching out by text. “While a voice hotline has its benefits, traditional telephone calls are no longer native communications for many young people,” she said. “Texting is where they turn first. That’s especially true for many at-risk communities, including LGBTQ youth and people with disabilities.”

The first-month performance metrics of 988 Lifeline revealed a predicted jump in volume. Compared to August 2021, August 2022 experienced a 45 percent increase. SAMHSA funds the hotline, and the nonprofit Vibrant Emotional Health runs it with a network of about 215 accredited centers. Roughly 59 of the centers also provide text and chat support (13). All 988 calls automatically route to the nearest accredited 988 Lifeline contact center by area code (based on the contacting phone’s area code) unless callers press 1 to reach the Veterans Crisis Line, the national crisis call system operated by the Department of Veterans Affairs, 2 for Spanish, or 3 for specialized support for LGBTQ youth. The overall answer rate in July 2022 was 83 percent compared to 92 percent in February 2023. Since launch, most outreaches to 988 have been by phone call, with an average answer rate of 86 percent compared to 95 percent and 98 percent for text and chat, respectively (14).

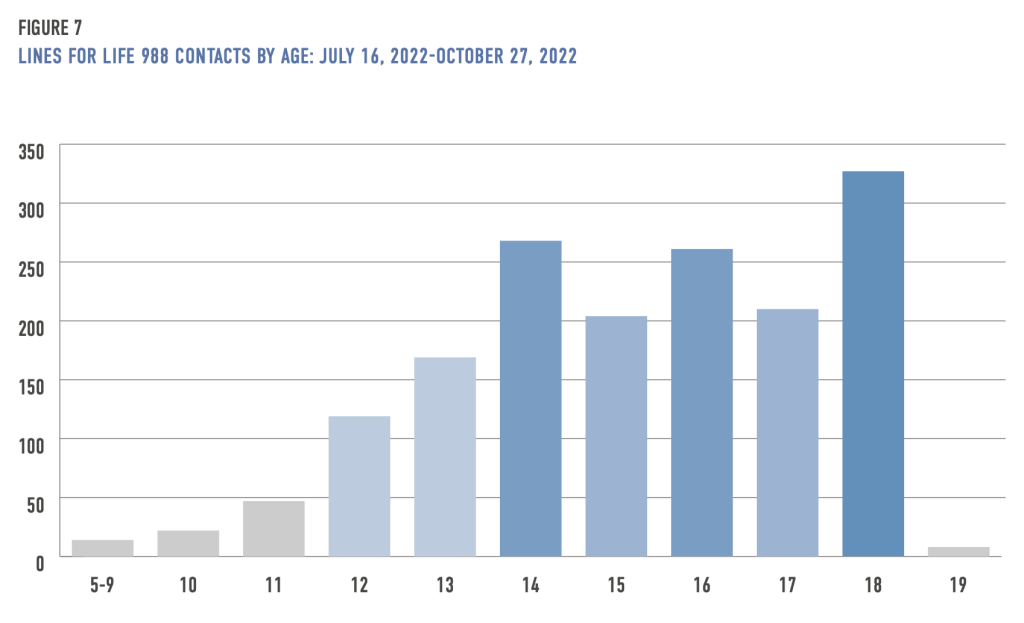

Vibrant Emotional Health does not collect national demographic data, so it is unclear, with 988 now live, how Lifeline call volume changed among young people nationally (15). However, Lines for Life, which answers 988 calls and texts in Oregon—and is a nationwide backup center for 988—received 1,655 calls, texts, and chats for youth ages 0 to 18 between July 16, 2022, and October 27, 2022 (16). The largest number of contacts to the 988 center was for teens ages 14 to 18, with the highest being 18-year-olds (327), followed by those ages 14 9268) and 16 (261).

Youth-focused crisis intervention, suicide prevention, and support lines like YouthLine and the Trevor Project help stabilize and mitigate crises for young people. According to Dwight Holton, executive director at Lines for Life, which offers YouthLine, pandemic data has reinforced what he already knew—that young people need peer-to-peer connection. He stated that federal, state, and local leaders must make peer services central to their 988 infrastructure. “Evidence has told us time and time again that peer-delivered services are most effective,” he said. Historically, the only available Lifeline off-ramp was for callers wanting to contact the Veterans Crisis Line (callers press option 1). Today, 988 callers can also press option 2 to reach a native Spanish-speaking counselor and option 3 to connect with specialized support for LGBTQ young people under 25. Holton believes adding peer-to-peer support and other special populations off-ramps would be similarly beneficial. At present, only those with an Oregon area code have direct access to the peer-service YouthLine by dialing or texting 988. Otherwise, young people must outreach YouthLine directly by calling 877-968-8491, texting “teen2teen” to 839863, or through chat or email (teen2teen@linesforlife.org). Teen peers are available from 4 to 10 p.m. PST. On off hours, adults answer the service. In Washington State, 988 callers can press option 4 to connect to the Native and Strong Lifeline, a line dedicated to serving American Indian and Alaska Native people.

The Trevor Project is a free and confidential crisis service available 24/7 for LGBTQ youth under 25. Its 2021 annual report stated that 201,000 people contacted the Trevor Project via phone, text, and chat. In addition, the nonprofit does surveys that give vital insight into challenges and protective factors for LGBTQ youth. For example, its 2022 national survey revealed that 45 percent of nearly 34,000 participants (ages 13 to 24) seriously considered attempting suicide in the past year. The percentage rose to 56 percent for children who came out about their sexual orientation before age 13, and 22 percent reported they attempted suicide within the past year. However, the survey found that family support plays a critical mitigating factor, revealing that attempted suicide was half (11 percent) for children who came out before 13 and had high family support.

This past fall, 988 Lifeline also launched a pilot for LGBTQ youth and young adults under 25, with the Trevor Project as the primary service provider. The service is available 24/7 by call, text, and chat. Callers press 3 to reach the specialized support.

The Trevor Project is a free and confidential crisis service available 24/7 for LGBTQ youth under 25.

Congress’ intent with the National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020 is far broader than the 988 number or even the 988 Lifeline accredited contact centers. The aim is to create a parallel system to the emergency medical model, including core counterparts to 911 call centers, emergency medical services, and emergency departments. According to SAMHSA’s National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care, behavioral health crisis systems should include regional or statewide behavioral health crisis call centers that coordinate in real-time, centrally deployed 24/7 mobile crisis, and 23-hour crisis receiving and stabilization programs. The National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020 allows states to use a monthly telecom customer service fee to cover 988 crisis system costs—not only costs to ensure efficient and effective 988 call routing to an appropriate crisis center but also those related to personnel and providing acute mental health, crisis outreach, and stabilization services by directly responding to the 988 hotline.

6 Statewide Youth Mobile Crisis, Partnership, and 911 Diversion

Tim Marshall, former director of Community Mental Health at the Connecticut Department of Children and Families, said that while 988 Lifeline can stabilize most calls, children and adolescents are more apt to need in-person care. This is partly because people outreaching mental health crisis lines for youth are often third parties, not the child or adolescent in crisis. For example, callers are often parents or school officials. According to Marshall, depending on a person’s perception of another comes with inherent pitfalls, with callers’ own biases or issues potentially influencing their perception. For example, a parent might be experiencing their own crisis.

To illustrate his point, Marshall shared “the peanut butter and jelly sandwich incident” when a parent called the Connecticut mobile crisis line because their child would not eat a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. When the clinician arrived on the scene, they quickly discovered that both the parent and child were in a mental health crisis. The face-to-face interaction, noted Marshall, revealed information the phone call did not. That’s why he is adamant mobile crisis must go out and do face-to-face assessments and why Connecticut’s statewide youth mobile crisis intervention service has a “just go” approach.

To ensure young people in crisis get behavioral health care instead of criminalization, it is dire that there are partnerships and connectivity between schools and behavioral health services and between 911 and 988.

The United Way of Connecticut/211—the state’s largest information and referral system—answers Connecticut’s 988 calls. The center can connect those contacting 988 with the statewide youth mobile crisis intervention service. Someone calling 211 can use an off-ramp by pressing 1 to reach youth mobile crisis services. According to Marshall, callers are typically connected to a call specialist “within 30 seconds.” Since the launch of 988, calls from Lifeline to the statewide youth mobile crisis intervention service have increased slightly, while 211 calls (through the 211 off-ramp) have remained roughly the same (18).

To ensure young people in crisis get behavioral health care instead of criminalization, it is dire that there are partnerships and connectivity between schools and behavioral health services and between 911 and 988. That’s why some communities like Austin, Harris County, Los Angeles County, Tucson, and Virginia have developed call matrixes to divert behavioral health calls and develop standardization. The levels correspond with perceived call risk and response. For example, in Virginia, Level 1 (routine) and Level 2 (moderate) go directly to the 988 contact center, while Level 4 (emergent) corresponds with the dispatch of emergency medical services or police, depending on the situation. According to Alexandria Robinson-Jones, the Behavioral Health (MARCUS Alert) Program and Training coordinator at Virginia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services, a Level 3 (urgent) requires a more nuanced approach, including tailored responses for special populations such as people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and children and adolescents. “That might mean looking to REACH teams for people with developmental disabilities or our children’s mobile crisis teams,” she said (19). “Incorporating specialized teams helps ensure that people have the response they need and that law enforcement isn’t automatically dispatched.”

According to Whitney Bunts, senior director of Public Policy at True Colors United (a nonprofit co-founded by Cyndi Lauper to meet the needs of LGBTQ youth facing homelessness), youth mobile crisis services are a vital tool for decriminalizing mental health (20). As with all U.S. systems and institutions, there is institutional racism in schools. They often default to ineffective and discriminatory zero-tolerance policies, contributing to the school-to-prison pipeline, with Black and Brown students disparately disciplined (21). Additionally, many schools have a police presence but lack in-school mental health services, making it more likely that students experiencing mental health challenges are criminalized instead of receiving care.

While the COVID pandemic has increased the focus on school mental health and trauma-informed approaches, a 2015 lawsuit in Los Angeles created the precedent that schools must do more to address student mental health. When a 17-year-old teen began sleeping on the roof of his high school, the school administrator suspended him instead of trying to connect him to care and told him that police would get involved if he returned. The teen, and other students and teachers in the Compton Unified School District, sued the district, arguing that students have a fundamental right to school-based mental health support. The school district serves a large minority student population—79 percent Hispanic and 19 percent Black. The lawsuit cites that the district did not adequately train teachers and administrators “to recognize, understand, and address the effects of complex trauma.” Mark Rosenbaum, attorney for the plaintiffs and director of Public Counsel’s Opportunity Under Law Project, likened the need for school-based mental health support to building ramps for children in wheelchairs.

The students and teachers won the class action against the school district, alerting school districts nationwide that they must address student trauma. According to Bunts, some school districts were moving away from punitive methods toward trauma-informed care when the pandemic hit. However, many have maintained their usual approaches. Marshall agrees, stating that kids experiencing mental health or substance use challenges continue to face school detention, suspension, police or ambulance, or expulsion. “Those are the default responses,” he said.

As previously mentioned, 87 percent of public schools participating in the School Pulse Panel survey reported the pandemic negatively impacted student socio-emotional development, and 84 percent said it harmed behavioral development (22). An evidentiary review of zero-tolerance policies by the American Psychological Association revealed the policies do not reduce the likelihood of disruption. Instead, school suspensions predict higher future rates of misbehavior and suspensions among suspended students. Sharon A. Hoover, PhD, co-director of the National Center for School Mental Health at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, has said that kids might be unable to communicate the challenges they are facing. “Students may not be aware that their behavior is a manifestation of an emotional or behavioral issue or trauma history, so that’s not something they are likely to communicate to teachers or administrators.”

An increase in student mental health challenges during the pandemic, along with ongoing zero-tolerance policies, creates a perfect storm of student trauma and behavioral health challenges, continuing to result in discipline instead of care. That’s why Connecticut developed a school-based diversion initiative. The Child Health and Development Institute of Connecticut, hired by the state, partners with school districts experiencing the highest number of arrests, data provided by Connecticut’s judicial system (23). The initiative features child development training and a school dashboard with attendance, detention, expulsion, and suspension data. Partnering schools now frequently default to calling the youth mobile crisis service instead of law enforcement and, depending on the school, have experienced a 40 to 90 percent drop in school arrests.

Many colleges and universities also have problematic responses, defaulting to legal self-protection and pressuring suicidal students to withdraw instead of trying to meet their students’ mental health needs. Misha Kessler was a sophomore at George Washington University in D.C. when he attempted suicide and learned of the school’s then forced withdrawal policy. Universities, including Brown, Stanford, and Yale, have pressured students in crisis to withdraw. “Students are deterred from getting the help they need if they fear that by doing so, they will be forced to withdraw from school,” he said. “It puts students at grave risk because many won’t seek help on account of the policy, and it punishes those who do.”

According to Dr. Hoover, schools and the mental health sector share the responsibility for student mental health. A comprehensive in-school support system includes a school psychologist, counselor, and social worker. She said community mental health partners “based in the schools” should augment school efforts. Schools are also a predominant referral source for youth to mental health services, including in-home crisis stabilization programs, which help stabilize kids experiencing a mental health crisis at home.

Another vital partnership is between primary care and behavioral health specialists. As previously mentioned, there is a shortage of child psychiatrists. In contrast, across the U.S., families can often get a same-day appointment with their child’s pediatrician. Dr. John Straus saw this as an opportunity for health care integration. So he developed the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program, which provides pediatric primary care providers with an 800 number (regionally designated to ensure connection to local services) that gives them access to a psychiatrist and referral assistance. “Within 30 minutes, a provider can speak with a child psychiatrist,” he said. According to Dr. Straus, the primary care doctor can usually meet the young person’s immediate needs, whether they need medication or assessment. However, some cases are trickier.

Today, child psychiatry access programs exist in 46 states, four territories, and two American Indian tribes.

For example, the pediatrician might see a child recently discharged from inpatient hospitalization. They need a medication refill, but the soonest appointment with a mental health provider is months away. “A pediatrician might call us and say, ‘I’ve never prescribed this antipsychotic,’” said Dr. Straus. “We will walk them through the dosage and ask how the child is doing. If they are stable, then they can refill it.” The psychiatrist can also do a telehealth consultation with the patient if needed.

Today, child psychiatry access programs exist in 46 states, four territories, and two American Indian tribes. The National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs maps out the state programs and whether they have 2018 and/or 2021 Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) funding.

In Massachusetts, the Department of Mental Health bills commercial insurers for the consults; roughly 60 percent of the children and adolescents have commercial insurance, and 40 percent have Medicaid. In some states, like Washington State, all insurers, including public insurers, must pay their fair share of the state’s child psychiatry access program.

Dr. Straus has said pediatricians often call the access line to determine whether they should send a young person to the emergency department. The psychiatrist will ask what assessments the pediatrician has done and, if needed, walk them through how to do them. “This helps them expand the tools they use in their practice and helps a family avoid sitting in the emergency department.”

7 In-home Crisis Stabilization and Peer Family Support

When a psychiatric hospital admitted 15-year-old Reina Chiang, she had already been waiting in the emergency department for days. Once in inpatient hospitalization, she found that the experience was not treatment-focused. “It’s a short-term Band-Aid,” she said. “You’re just there for extended amounts of time, with people watching you. They’re primarily making sure you don’t harm yourself, and that’s it.”

When appropriate, in-home crisis stabilization is far more cost-effective and better for youth.

According to Andrea Rifkind, inpatient psychiatric hospitalization is not the right level of care for most children and adolescents. “Hospitals are intended for acute, not long-term, stabilization,” she said, pointing out that hospitalization and juvenile detention derail a young person’s support system and education. Rifkind is the program director at Sheppard Pratt Health System’s Care and Connection for Families, an in-home crisis stabilization program in Montgomery County, Maryland. Stabilizing children and adolescents in their homes diverts them from the emergency department, inpatient hospitalization, and juvenile detention and allows them to remain engaged in their life and build resiliency. It is also less costly, personally and financially. “When appropriate, in-home crisis stabilization is far more cost-effective and better for youth,” she said.

Care and Connection for Families is a fully grant-funded, in-home crisis stabilization program for young people ages 5 to 18 experiencing a mental health crisis. The program provides short-term, whole-family crisis intervention and counseling services. The majority of their clients are Hispanic or Black.

For much of the pandemic, the average client age was 13 to 14; however, it dropped to 12 in the fiscal year 2023 (July 2022 – June 2023). There are other shifts as well. For example, throughout the pandemic, the program has received school referrals for elementary school students expressing suicidal ideation. Lately, the program is also getting more referrals for students experiencing school avoidance because of their mental health needs (24).

Kids enter the program through school referrals (its largest referral source), after discharge from a hospital, or as a step down from a residential treatment center. Treatment lasts between 8 and 16 weeks and connects the child to long-term services. With a budget of roughly $1 million and 8 full-time staff (4 therapists and 4 in-home stabilizers), the program serves 120 kids and their families annually. The in-home stabilization program has also received a grant for Central and South American newcomer youth in crisis, allowing them to serve 60 young people ages 5 to 18 and their families.

In-home stabilization comprises a two-person team—a therapist and an in-home stabilizer. The child and therapist set therapeutic goals; the in-home stabilizer reinforces these goals. Rifkind calls the in-home stabilizers the program’s “secret sauce”—they act as case managers and mentors and help connect families with food, clothing, and housing. “When we have a family whose basic needs aren’t being met, which we see every day, it’s very hard for parents to focus on mental health needs.” While some children and adolescents might need hospitalization, Rifkind has found that hospitalization withdraws them from their natural support system, connections that might be a protective factor in their life. “In our experience, young people are comfortable in a less formal, traditional therapeutic space.”

Matching young people to prompt care can lower their suicide risk. According to a study published in JAMA, follow-up care within seven days after hospitalization reduces suicide risk by 56 percent for children and adolescents. However, Ebony Chambers, Chief Family and Youth Partnership Officer at Stanford Sierra Youth and Families (SSYF), shared that families and caregivers of youth are often left out of the dialogue. “You can’t address a child’s crisis without addressing family dynamics,” she said. “That’s not because parents or siblings don’t want the child to get better but because we often don’t know what’s triggering them in the first place.” Furthermore, when a child is in crisis, so too is the family.

Parent peer support is what helped Chambers as she navigated the crisis system with her daughter. “Someone else was coming in with letters and numbers behind their name, and that was great,” she said. “They had the clinical expertise, but there’s nothing like someone sitting on the floor with you while you’re crying, and they understand what you’re going through.” She found the service so vital that she brought it to her organization, adding 40 parent peers across five counties in Northern California. During the pandemic, Zoom has allowed the parent peer support service to expand its reach. The organization serves about 5,913 youth and families; most have Medi-Cal, though, in 2021, SSYF acquired a contract with Kaiser Permanente. Chambers hopes other commercial insurers do the same. “We know what families get when they go through their private insurance isn’t sufficiently comprehensive.”

8 Conclusion: Young People Need Connection to Services, Support, and One Another

Emergency department use is the canary in the proverbial health care coal mine. Psychiatric boarding for young people has long been an issue nationwide, with children and adolescents deteriorating in the ED, waiting for a connection to care for hours, days, or months. During the pandemic, where youth experienced increased challenges during developmental milestones, spikes in child and adolescent mental health and substance use disorder ED visits have illustrated chasms in behavioral health care, a byproduct of thrusting youth into systems built for adults. Continuing to do so will reap the same challenges, marginalizing children and adolescents in crisis, with law enforcement and the emergency department as the default responder and provider, respectively. However, 988 is an opportunity for state and local leaders to scaffold youth-based crisis services that are interconnected, ones that provide person-to-person care and allow children and adolescents to remain in their day-to-day lives, so they have continued access to their education, peers, family, and other supports. Vital crisis services and supports for young people include youth mobile crisis services, in-home crisis stabilization (which serves the young person and their family), 988 connection or off-ramps to peer-to-peer and special population crisis intervention and support lines, primary care-child psychiatry access programs, robust school-mental health partnerships, and 911-988 diversion. These services and supports make treatment more accessible and minimize potential disruption to a young person’s life.