1 Introduction

Central to any meaningful redesign of health care is a discussion of our workforce. Who is doing what, to whom, where, and at what cost? Most policy solutions tend to focus on the supply of our workforce: How many clinicians do we have and where are they located? The answers to these questions often leave decision makers wanting more, because the answers tend to always be the same: We need more clinicians and we need them everywhere, especially in places they are not, such as rural areas. However, as we describe in this paper, there is a different way to think about workforce—one that takes some of the burden off our traditional clinical systems and licensed clinicians to allow for others to begin to assist with these critical health needs. Simply put, we may be asking the wrong questions about workforce. Instead, we may need to begin to think about a new strategy for addressing community need: a new workforce that emerges in community, by community, and for community.

Even before the current public health crisis of COVID-19, finding access to mental health services was difficult. And although COVID-19 has offered a rare moment for the country to reflect on our public health and health care infrastructure and to examine the deficits laid bare, it has not yet brought forward many solutions for mental health services. Likely the most relevant intervention has been the loosening of telehealth restrictions to allow more clinicians to bill for services they deliver both by telephone and by video platforms. The mental health community has taken full advantage of this temporary change, as demonstrated in recent data from the Commonwealth Fund, which show mental health clinicians utilizing telehealth interventions at much higher rates than other specialties (1). This temporary policy change helps because there was an access issue prior to COVID-19, and with the increase in reported mental health symptoms, technology has helped address some facets of our collective need specific to access—but work remains.

The goal of this paper is to provide a framework for the mental health and addiction workforce in the United States. It proposes three shifts that need to take place at the clinical, community, and individual levels to adopt the proposed framework and achieve our goal of population health. This paper focuses on laying out the proposed framework and policy considerations that can reconceptualize workforce to enhance the overall capacity of our clinics and our communities in addressing mental health.

2 Understanding the Problem

Why must people wait so long to receive care? A major contributing factor is that we have a fragmented system that has created barriers for people who have mental health needs. From the way our health insurance is designed to the way care is delivered, mental health and addiction care is seen as a separate specialty from primary care, making it more challenging for a person to get timely access to care. For example, our health insurers have networks of clinicians available for their beneficiaries, and while these clinicians are listed as being part of a network, many are booked up for weeks if not months or simply do not take new patients. These issues of coverage and availability affect us all, but especially those who have the most pressing or acute needs.

From the way our health insurance is designed to the way care is delivered, mental health and addiction care is seen as a separate specialty from primary care, making it more challenging for a person to get timely access to care.

Thirty-three percent of individuals who seek care wait more than a week to access a mental health clinician, 50% drive more than one-hour round trip to mental health treatment locations, 50% of U.S. counties have no psychiatrist, and only 10% of individuals with an identified substance use disorder receive care (2). And while these statistics are daunting, they focus only on identifying a provider. When families eventually find care, they are likely to face other barriers; for example, mental health office visits with a therapist are five times as likely to be out of network, compared with non–mental health office visits (2). These barriers are often more significant in communities of color, particularly the Black community, and often result in more severe mental health concerns due to unmet needs. High rates of serious psychological distress reported among African Americans and increasing suicide rates (3) are among the growing disparities that are systemic and that can be attributed to centuries of racism (4), which will require much attention.

Lack of insurance and—despite the mental health parity law—a continued lack of coverage for mental health services on par with other medical services for individuals who are insured have long left many without access to necessary care. In addition to an overall shortage of mental health professionals, maldistribution of providers magnifies this barrier to accessing care in certain areas, particularly rural communities. Inadequate compensation and financing models that are volume-based, as opposed to value-based, may further complicate workforce dynamics—as there are limited incentives to enter the mental health profession. The high cost of training and student loan debt may also create barriers for mental health practitioners to participate as Medicaid providers, because Medicaid payment yields on average only 52% of private insurance and providers must be able to cover their costs to remain viable.

Although there is great variation across U.S. states, as well as counties within states, current and projected workforce numbers for mental health professionals raise some concern (5), and efforts to document workforce gaps and expand the provider base to meet the growing need has posed challenges (6). A recent congressionally mandated report by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) found that some professions (psychiatrists and addiction counselors) were expected to continue to experience shortages between now and 2030, whereas other professions (nurse practitioners, physician assistants, psychologists, social workers, marriage and family therapists, mental health counselors, and school counselors) would have sufficient numbers and in some cases have an oversupply (5). The report states that these projections are a baseline scenario and based on the assumption that there would not be any changes in the level of mental health care service provision or utilization by 2030. In 2017, it was impossible for the authors to predict that a global pandemic would strike, crippling our health care systems and wreaking havoc on our nation’s mental health.

There are also concerns related to the diversity of the mental health workforce. Because only 6.2% of psychologists, 5.6% of advanced practice psychiatric nurses, 12.6% of social workers, and 21.3% of psychiatrists are members of minority groups (7), increasing the number of providers who reflect the demographics of the community they are serving is key to addressing gaps in linguistically and culturally competent care. These factors, paired with an aging workforce looking toward retirement, highlight the challenges facing the mental health service delivery system (8). Recent projections from HRSA underscore the need to focus on the multitude of factors affecting the mental health workforce to meet the growing need (5).

3 A Call for a New Workforce Framework

To meet the ongoing demand for mental health and addiction services, we need to think differently about our workforce. Simply relying on our licensed clinicians will not allow our communities to get ahead of the problem and more proactively address mental health needs. In addition, because our health care system often forces us to wait until there is a problem (and a diagnosis is given), for many of us help comes too late. Broadening how we think about our workforce allows for more timely interventions in the places people are showing up with mental

health needs.

Broadening how we think about our workforce allows for more timely interventions in the places people are showing up with mental health needs.

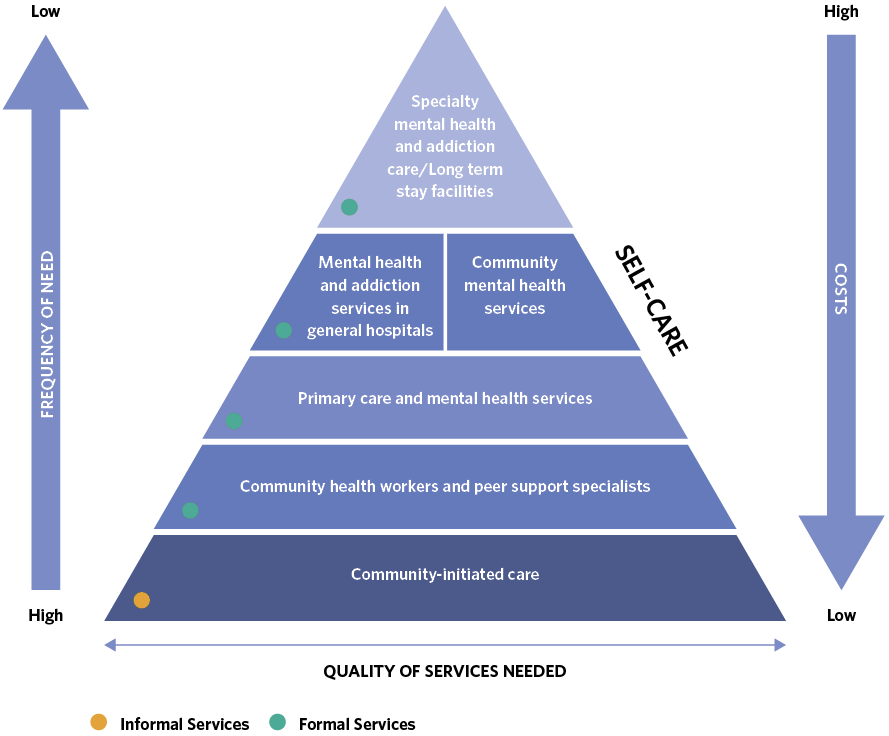

We present the following framework for addressing shortages in the mental health and addiction workforce in the United States. As seen in Figure 1, mental health services, as well as need, exist on a continuum. A continuum does not imply a hierarchy. Rather, the figure is meant to show the interconnectedness between various elements of the workforce and how they complement one another. Individuals will have needs that fall along the continuum, depending on their willingness to seek services, their health insurance coverage, and severity of need.

The framework calls for three majors shifts in the health care workforce to address the increasing demand for mental health and addiction services and the limited capacity: 1) a shift at the clinical level to manage more mental health and addiction services in primary care, 2) a shift at the community level to expand the community-based workforce in mental health and addiction care across clinical and public settings, and 3) a shift at the individual level to train the lay public in low-level psychological interventions.

This shift is not to be seen as replacing needed access to health care or clinical services – but complementary support through community-based structures for a system that is overburdened. This approach may provide a sufficient level of care for some, and an entry point to clinical care for those who have needs that are currently unaddressed. The framework proposes that shifting mental health care away from specialty care and toward the community and primary care would also create a shift toward high-frequency, low-cost interventions. Here we describe challenges, opportunities, and policy considerations for each of these recommended shifts to reconceptualize the workforce to enhance the overall capacity of our clinics and our communities.

Figure 1.

Framework for Mental Health and Addiction Workforce (revised from WHO [9])a

Mental health care initiated by lay individuals in the community should be performed frequently, followed by care coordinated by a community-based mental health workforce, mental health services in primary care, short-term stays in general hospitals for acute mental health care, and, finally, specialty care and long-term stay facilities.

4 Policy Considerations

Clinical Level: Shift Mental Health and Addiction Services to Primary Care

Although primary care often serves as the entry point for identifying and managing mental health concerns, and primary care physicians (PCPs) prescribe a significant volume of mental health medications, most PCPs receive little training in mental health and are often not well equipped or supported to offer the most effective care (10, 11). Psychiatrists and addiction specialists remain in short supply—underscoring the need to integrate mental health and addiction treatment into primary care and ensuring that those providers have the skills to screen, assess need, and provide treatment or refer as needed (5). Bringing mental health services into primary care represents one of the first shifts we need for our workforce—to bring our clinicians to the places people are. Primary care is the largest platform for health care delivery, offering an access point where people can have their mental health needs identified and treated. Further, bringing mental health care on site decreases the amount of visits a person will have to make to find help and increases the likelihood that they receive the care

they need.

Bringing mental health services into primary care represents one of the first shifts we need for our workforce—to bring our clinicians to the places people are. Primary care is the largest platform for health care delivery, offering an access point where people can have their mental health needs identified and treated.

The integration of mental health and addiction care (commonly referred to as “behavioral health” care in the clinical community) with primary care is defined as an interdisciplinary team of providers, who work together with patients and families to deliver a systematic and cost-effective approach to addressing mental and substance use disorders; health behaviors that fall short of a diagnosis, but contribute to physical conditions; life stressors and crises; stress-related physical symptoms; and ineffective patterns of health care utilization (12).

Health integration can vary depending on the patient population, provider type availability, and financial and technological resources, but integration usually consists of a set of core components.

These components include:

- systematic screening

- team-based care

- ongoing care management to ensure coordination between providers and patient

- measurement-based care that uses symptom rating tools to adjust treatment as needed

- patient information exchange between providers

- links to social services

- patient education to promote self-management of health conditions

- systematic quality review of integrated care delivered by the provider/practice (13, 14).

One highly studied integrated approach is the collaborative care model, which introduces a care coordinator and mental health consultant into a primary care practice (15). This model, in which providers work together either on site or virtually to care for patients through established relationships, exemplifies a team-based approach and can provide valuable expertise to primary care, especially in regions with shortages of behavioral health providers (16).

Health integration has been shown to improve depression outcomes (17, 18), reduce hospitalizations and emergency room visits (19), and improve management of diabetes and hypertension (20). Some evidence suggests that integrated care can result in cost savings at the level of practices and payers, as well as statewide initiatives (19, 21, 22, 23). There is even some evidence to suggest that integrated care can improve access and mental health outcomes in communities of color, which could be important for reducing mental health disparities in these communities (24, 25, 26).

As state and federal leaders develop policies to advance the integration of mental health and addiction services into primary care, there are a range of licensing, training, and payment issues that should be considered. Such considerations are summarized below:

- Redefine primary care to explicitly include management of mental health and addiction services. This change could take place through state or federal legislative or regulatory action to define a set of common expectations for delivering integrated care for providers, patients, and payers. This new standard could be implemented across state and federal health agencies and facilitate additional changes in the financing and delivery of primary care, inclusive of behavioral health services.

- Expand integrated care training opportunities for the current and future workforce. To further advance integration, key providers, such as primary care providers, behavioral health care providers, and care managers and coordinators, require training in integrated care. Current federal grants that support opportunities for behavioral health providers and paraprofessionals to train in integrated settings could be expanded to meet increasing need for behavioral health integration (27). State or federal policy makers should also consider funding technical assistance and training opportunities to train current providers and practices interested in implementing integrated care.

As state and federal leaders develop policies to advance the integration of mental health and addiction services into primary care, there are a range of licensing, training, and payment issues that should be considered.

- Enhance team-based care by considering changes to state licensure reciprocity and expanded scope of practice. A number of states have expanded licensure reciprocity and scope of practice as a result of COVID-19 in order to expand provider capacity (28). States and national stakeholders should evaluate how these changes have affected access to mental health and addiction services and their impact on quality of care. After evaluation, states and national stakeholders could consider making policy changes to permanently expand scope of practice for specific providers, increase state participation in licensure compacts, and expand participation in mutual reciprocity between states—or stakeholders could develop a nationally recognized application for state reciprocity. These policy changes could expand the capacity for mental health and addiction providers to participate in virtual consultation roles with primary care practices or otherwise work as part of a virtual team.

- Reform current payment mechanisms to support training and start-up costs associated with integrated care in primary care. Current payment models do not adequately support the hiring, training, workflow changes, and other start-up costs associated with introducing integrated mental health and addiction treatment into primary care (29, 30). Although a range of payment models could support integrated care, there is evidence that prospective payment mechanisms can be a cost-effective means of supporting integrated care (22).

Community Level: Shift Services to Peers and Other Nontraditional Community Workers

In addition to expanding the current clinical workforce, efforts to shift care into the community away from traditional clinical settings have been successful in prevention, recovery, and mitigation/harm reduction. In many cases, community workers may be effective in meeting the need for support, and in others they can serve as a bridge to additional resources or more intensive services. In addition to improving outcomes through evidence-based and cost-effective strategies, democratizing knowledge and skills to a larger set of community-based workers alleviates demand for a highly trained clinical workforce, ensuring that there are a multitude of entry points to a coordinated delivery system and that the capacity is there to provide the appropriate level of care across the spectrum of need.

In many cases, community workers may be effective in meeting the need for support, and in others they can serve as a bridge to additional resources or more intensive services.

Existing models that promote the benefits of situating mental, social, and spiritual support services within the community setting include community health workers/promotoras, peer support services, and other frontline public health workers, and these roles are described below.

Community health workers (CHWs)/promotoras (social and mental) are members of the communities they serve. As such, CHWs/promotoras have a unique vantage point, enabling them to better recognize and understand needs and reach those in need. Because they often live in the community, sharing the culture and language, they are often trusted and able to deliver culturally competent care. Evidence is mounting that these positions can positively affect the health of a community (31). The Nurse Family Partnership program (32) (such as Family Connects Durham [33]) is another example of an approach that provides support for new families and offers a multigenerational approach that has been shown to improve a variety of behavioral health outcomes and reduce risk through home visiting services.

A growing body of evidence demonstrates the great benefits of peer support services. There is an important element to both arms of this corps—to both sets of peers—where the “peer to peer” aspects of the work will be most impactful. For example, when recent high school graduates work with current high school students on the importance of mental health, this approach has a very different look and feel than more traditional routes for seeking and providing help. A focus on the benefits of peer support services does not minimize the importance of professional clinical services when they are needed. However, there are unique ways in which we can leverage the “peer” role around sensitive topics. A peer approach is particularly beneficial with youth, who have unique needs in the wake of COVID-19. School shutdowns have affected milestone events typically shared with friends and peers (graduation, prom, etc.), and social distancing has eroded some relationships. Going forward, there is still much uncertainty, and navigating all these feelings and new ways of life will be difficult, especially for young people. “Postvention”—rather than intervention—for young people should recognize their unique differences and struggles, and peer support models will be important for meeting these specific needs. Some states are leveraging a workforce that includes peers and other nonlicensed individuals within the Medicaid program (34).

COVID-19 has reintroduced the function of contact tracing into the national dialogue. Contact tracers help identify positive cases and track who else might have been exposed to a virus.

Finally, we should consider other frontline public health workers—such as contact tracers—who can play a critical role in managing a pandemic and addressing other population health issues. COVID-19 has reintroduced the function of contact tracing into the national dialogue. Contact tracers help identify positive cases and track who else might have been exposed to a virus (35). The combination of reopening our country and the deadly spread of the virus has made the function of contact tracers more important than ever. Calls have been made to increase our contact tracer workforce (36), and increased funding for the contact tracer program would allow for more tracers—providing communities with an enhanced economic opportunity as well as more accurate tracking of COVID-19 cases, which can help mitigate spread.

Contact tracers can play a critical role as a frontline resource for information on mental health and addiction by educating people about symptoms and assisting them in seeking help.

Contact tracers can play a critical role as a frontline resource for information on mental health and addiction by educating people about symptoms and assisting them in seeking help. Contact tracers do not need to be trained clinicians; instead, they rely on clear processes, including knowing how to screen and to respond to people who have positive screens and then referring or connecting them to the most helpful services. Most contact tracers have a working understanding of their communities, and thus they may have relationships with clinicians who can help address any issues that arise.

Without better assessing our nation’s mental health, we run the risk of countless individuals suffering alone and in silence. Although there have been positive changes to help, such as telehealth, we still need to do a better job of identifying those with need, and contact tracers can be a new first line of defense.

Policy considerations at the community level are summarized below.

- Ensure adequate funding for the community-based workforce. Provide a funding mechanism for compensating training and adequate salary for individuals who commit to delivering mental health care in communities, especially in designated communities with a lack of accessible care.

- Expand mental health and trauma-informed programs. Scale up a mental health and trauma-informed workforce in schools, health care settings, social services, and the justice system, as well as among first responders, and increase resources for communities.

- Prepare a training model for training public health workers. Contact tracers and other public health workers have a unique role to play in screening for COVID-19 and tracing COVID-19. As vaccines become available, they also have a role at distribution sites. They should be trained to screen individuals for mental health and addiction needs and to intervene and coordinate services.

Individual Level: Shift Toward Low-Intensity Interventions by the Lay Public as a First Line of Defense

In other countries where workforce issues are far greater than what we see in the United States, experts have begun to train community members on evidence-based interventions with their peers. This approach, often described in the literature as task shifting or task sharing, brings evidence-based techniques into the community so that the lay public are more empowered to help each other with mental health issues. Providing additional training to the lay public should supplement the existing health care system by enhancing the capacity of communities to address aspects of mental health and addiction on their own.

The lay public could be broadly divided into two categories: 1) individuals with frequent contact with other members of the community, including teachers, spiritual leaders, volunteers, or individuals in the service industry; and 2) individuals with low levels of contact with members of the community other than family, neighbors, and coworkers. This distinction could translate into different approaches to mental health training for the lay public.

A reformed mental health system would not only include integrating mental health and addiction services into primary care and community-based health care, but it would also enable and empower individuals to learn how to respond to mental health and addiction issues.

A reformed mental health system would not only include integrating mental health and addiction services into primary care and community-based health care, but it would also enable and empower individuals to learn how to respond to mental health and addiction issues.

To achieve this goal, members of the community without health care experience could be trained to use low-intensity, evidence-based, psychological tools to implement on themselves (self-care) or with others. This training would teach individuals interventions that could build on Mental Health First Aid trainings, which provide a baseline competency for understanding mental health conditions (37).

Training for individuals with roles that facilitate frequent touch points with others in the community would take advantage of existing relationships to provide a first line of support for individuals experiencing mental health issues. Training for the lay workforce has been implemented across cultural settings with volunteers or local members of the community with little or no health care experience to deliver low-intensity psychological interventions (38, 39). These interventions include the Common Elements Treatment Approach (CETA) and Problem Management+ (PM+), which teach skills, such as problem solving and managing stress and emotions, that can translate across common mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression, and that can be taught over short periods. There is evidence that both CETA and PM+ can improve outcomes for depression and anxiety (40, 41). Although these interventions have been performed in home and community settings (39, 41), studies have not necessarily examined whether expanding training to individuals in different societal roles or across a wider range of settings could yield similar improvements. The interventions required some supervision from a trained mental health professional, but telemedicine and virtual supervision were acceptable proxies (42).

There have also been grassroot efforts, such as the Confess Project, an organization that partners with barbers in Black communities around the country to provide training in identifying common mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression, as well as training in active listening, nontriggering language use, and healthy coping skills (43). For individuals who do not frequently experience long-term engagement with members of the community, training could focus on similar problem solving and stress and emotional management for people to use in their own lives, as self-care, or to informally coach friends and family. Schools could be an appropriate place to teach these skills to younger populations.

As states and federal leaders examine how to better equip individuals with tools for managing mental health needs in their lives and in their communities, the following policy issues should be considered.

- States and the federal government should invest in widespread mental health training for individuals. Given the acute mental health workforce shortages and the ongoing need for mental health care as a result of COVID-19, widespread training would equip members of the community with the tools to identify mental health conditions in their community early and provide low-level interventions. This training could be supported through federal grants, in partnership with states and the private sector.

- Outcome measures should be developed to accurately assess lay public interventions. The informal, and possibly varied, implementation of layperson psychological interventions could make it more difficult to assess effectiveness. One solution is to develop measures that focus on the experience of recipients and their ability to manage emotional and mental health as result of the intervention.

- Implement appropriate pathways for referrals to additional mental health services. In addition to interventions, the lay public should also be equipped to identify when a person needs additional help and how to provide referrals for appropriate care.

- Fund additional research on low-level mental health and addiction interventions in communities. The research on lay public mental health training is limited, but such training could result in an untapped first-order defense for addressing low-level mental health needs and connecting individuals to additional care (e.g., community-based care or integrated primary care). Additional research on lay public interventions for addiction care would be key.

5 Conclusion

If we are serious about stemming the tide of mental health and addiction need, we must begin to think differently about our workforce. The proposed framework would address workforce shortages in the short term by redistributing our current workforce into the places that people are and forming a multilayered, community-forward approach to mental health and addiction care that begins with each of us in community and reserves and protects specialty care for individuals with more complex needs. This framework would expand access by providing multiple entry points to mental health and addiction care and would reduce stigma by training all individuals in the community, regardless of professional mental health or addiction health training, to identify and respond to mental health and addiction needs.