1 Introduction

In recent years, major U.S. policy efforts have been aimed at combating the epidemic of opioid addiction and overdose deaths. This white paper focuses on the newest aspect of the epidemic, the increased use of fentanyl, and it proposes six strategies to deal with the public health consequences of misuse of this powerful opioid. In this time of health and social policy change, it is imperative that policymakers follow these six strategies to address the crisis.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have reported that the number of overdose deaths involving opioids has quadrupled since 1999; 91 Americans currently die every day from an opioid overdose (1). A primary driver of the epidemic has been the fourfold increase in sales of prescription opioids, such as oxycodone, aimed at improving pain management (2). The increases in opioid sales have not resulted in detectable reductions in reported levels of pain (3). In response to the epidemic, the medical community and policymakers at the federal, state, and local levels have attempted to intervene by using various approaches, including the release of new clinical guidelines on opioid prescribing and regulations on opioid dosing, establishment of and regulations regarding use of prescription drug–monitoring programs, pill-mill crackdowns and enforcement efforts, insurance changes to broaden access to evidence-based addiction treatment, and regulatory changes to expand the supply of physicians trained in addiction medicine, among other approaches.

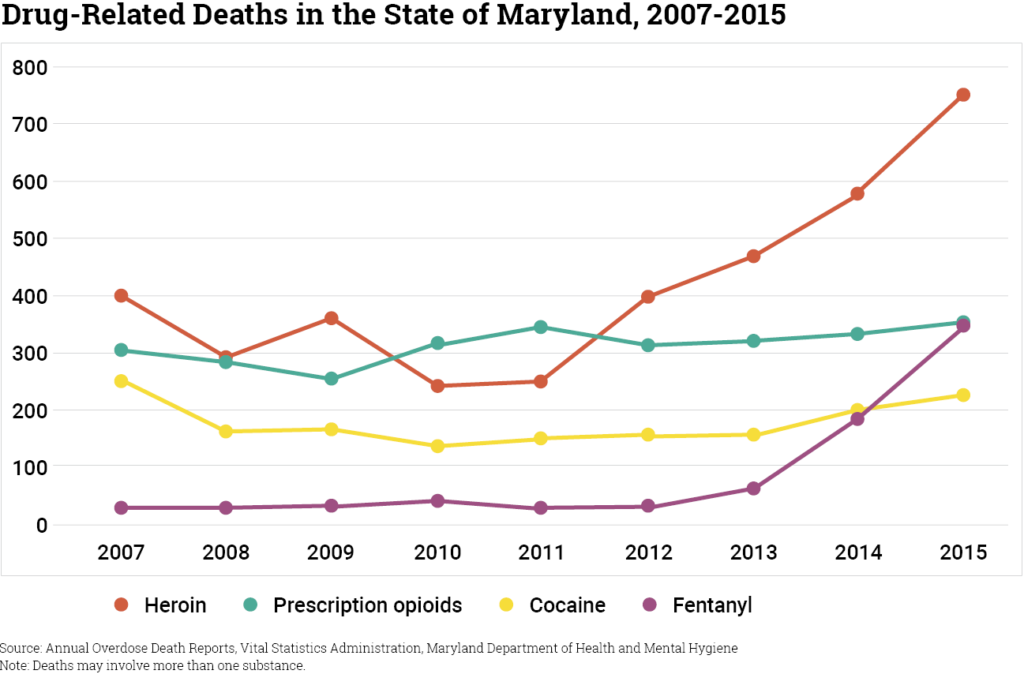

These multiple and varied approaches have changed rates of opioid prescribing, and they appear to have shifted the types of opioids involved in overdose deaths. However, they have done little to reverse the increase in mortality related to opioid overdose. One factor that has complicated efforts to control overdose deaths has been the emergence of the public health crisis related to illicit fentanyl, particularly when mixed with heroin and counterfeit oxycodone. Fentanyl is an opioid agonist for the treatment of severe pain (e.g., advanced cancer pain), with a potency 50 to 100 times that of morphine. The share of opioid overdose deaths involving fentanyl has increased rapidly over the past few years. For example, in Maryland, the number of deaths due to fentanyl rose sharply from 2013 to 2015, (see figure). A portion of the increase in heroin-related overdoses involved fentanyl mixed with heroin. In Rhode Island, 50% of the 239 opioid-related overdose deaths in 2015 involved fentanyl, compared with 37% of the opioid-related overdose deaths in 2014; in prior years, less than 5% of opioid-related overdose deaths in the state involved fentanyl (4). Although some pharmaceutical fentanyl is diverted, illicitly manufactured synthetic fentanyl (which includes multiple new fentanyl analogues) has been implicated in overdose deaths in multiple states.

A number of features of fentanyl contribute to its devastating public health consequences. First, it is highly potent, which means that a small amount can cause respiratory depression and rapid death. Second, production costs of fentanyl are comparatively low, creating an incentive to mix fentanyl with heroin or other illicit narcotics. Third, the incentive to mix fentanyl with other drugs means that many individuals are not aware that they are consuming fentanyl (5). In addition, anecdotal evidence suggests that drug suppliers may not be aware that their products contain fentanyl. Fourth, the rapid lethality of fentanyl means that the traditional approach to overdose rescue with naloxone may no longer be adequate. Naloxone is a medication that can effectively help a person experiencing a life-threatening overdose. However, when the overdose involves fentanyl, naloxone seems to require quicker administration and often multiple doses, compared with rescue from overdose of other prescription opioids or heroin (6).

The recent rise in fentanyl-related overdose deaths suggests that new approaches are needed to combat the opioid epidemic, including adoption of harm reduction strategies.

2 Six Specific Strategies Should Be Considered as Part of Efforts to Combat the Opioid Crisis

1. Safe Drug Consumption Sites

Safe drug consumption sites are spaces where substance users can legally use pre- obtained drugs under medical supervision in a safe environment. Safe consumption sites strictly forbid drug sharing or selling. Research findings from a safe consumption site operating in Vancouver, Canada, support the role of consumption sites in reduced overdose mortality (7) and public disorder (8) (e.g., public syringe disposal) in the surrounding neighborhood without increased local crime or drug use (9). These sites are viewed as a bridge to connect marginalized individuals to critical supports, including drug and HIV treatment, primary healthcare, housing, and other social services. Research showed that individuals who used safe consumption sites had greater use of detoxification services relative to a comparison group (10). A number of U.S. communities are considering establishing safe consumption sites, including Baltimore, Seattle, San Francisco, and Ithaca. Operation of these programs depends on gaining buy-in, including with law enforcement, in their communities.

2. Anonymous Drug-Checking Services

Drug-checking technology is a harm reduction approach intended to reduce the likelihood of fatal overdose from consumption of products containing fentanyl or other substances. These services provide individuals with information on what drugs contain prior to use. Testing can occur at safe consumption facilities or other locations (e.g., festivals). Anonymous drug-checking services have been implemented in various European countries, where guidelines have been developed (11). Drug checking provides individuals with information to demand safer products in street-level transactions and can be used to identify contamination at various points in the supply chain (sellers and buyers).

3. Updated Naloxone Distribution Policies

Because fentanyl overdoses require more rapid naloxone administration and may require multiple doses, an updated approach to overdose prevention using naloxone is needed. Frank and Pollack noted the importance of naloxone kits with higher dosages and user-friendly formulations (e.g., auto- injectors), as well as the need to increase their availability to users (12). One promising approach—take-home naloxone—often requires changes in state pharmaceutical regulations (13). Other policy approaches aimed at improving rapid access to naloxone that communities might consider include training first responders (police and EMTs) to use naloxone, providing naloxone to friends and family members of people using opioids, enacting legal protections for people who call for medical help for an overdose, and enacting legal protections for laypeople who administer naloxone. Adoption of these policies is dependent on state regulations, and some states, such as Rhode Island, have developed model approaches (14).

4. Harm Reduction-Oriented Policing

One promising development has been the movement within law enforcement to more closely align drug-related policing practices with public health efforts. Harm reduction-oriented policing involves altering law enforcement responses to behaviors that do not pose significant public safety concerns, such as simple possession of a controlled substance. The approach is designed to reduce the harms associated with prosecution of low-level crimes.

For example Seattle’s Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) Program is a pre-booking diversion program that involves law enforcement officers’ redirection of low-level offenders engaged in prostitution or drug use, diverting them from criminal justice settings to community-based health and social services with the intent of reducing human suffering and improving public safety. The program provides immediate case management, linking individuals to drug treatment, job training, housing assistance, legal advocacy, counseling, and other resources. Case managers also have access to funds to support other needs, including food, motel stays, and clothing.An evaluation found that relative to participants in a control group, LEAD participants had 1.4 fewer jail bookings on average per year after program entry and 39 fewer days in jail per year, and the odds of having at least one prison incarceration were 87% lower after program entry (15,16). Although pre-booking diversion can shift individuals from criminal justice settings to drug treatment and other social services, it is unknown whether these changes translate into a reduction in overdose deaths.

5. Targeted Expansion of Evidence- Based Pharmacological Treatments in Criminal Justice and Emergency Department Settings

Broadening access to pharmacologic treatment for substance use disorders, including methadone or buprenorphine (opioid agonists) and naltrexone (opioid antagonist), used in conjunction with behavioral therapies is critical to combating the overdose epidemic. However, in the context of growing concern related to fentanyl, targeted investments in expanding access in criminal justice and emergency department settings are particularly important for reaching individuals most at risk of fentanyl overdosing.

Incarceration provides multiple opportunities to intervene with individuals who use opioids and who are at risk of overdose, including initiating or continuing treatment on entry or transition to treatment on release. Medication-assisted treatment has been shown to enhance treatment engagement in correctional settings (17,18), and improve treatment participation, avert overdose, and reduce risk of relapse after release (19,20,21). For example, a randomized trial of methadone maintenance and counseling pre-release for persons incarcerated in a Baltimore correctional facility found that persons randomly assigned to methadone maintenance and counseling had significantly fewer days of criminal activity and heroin use after release, compared with those randomly assigned to counseling only (22). In practice, there are several barriers to treatment in correctional facilities, including constraints of a setting in which security considerations predominate, the deplorable conditions in many justice settings, and extreme resource constraints for non-security-related priorities. In addition, most U.S. correctional facilities that offer substance use disorder treatment rely primarily on non-pharmacologic treatments, such as peer support, therapeutic communities, or counseling only (18). Overdose-related mortality rates have been found to be significantly elevated during the weeks immediately after release from a correctional facility (23).

Expansion of the Medicaid program in 31 states and the District of Columbia under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has meant that many more individuals transitioning to the community from criminal justice settings are now eligible for Medicaid. In justice settings, it is thought that individuals with opioid use disorders who have immediate access to Medicaid upon release will be more likely to enter treatment and less likely to re-offend. To facilitate access to Medicaid, a number of jurisdictions have begun efforts to screen for Medicaid eligibility while an individual is incarcerated (24). A study by Saloner and colleagues found that in the first year following implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014, the uninsurance rate among justice-involved individuals with substance use disorders declined from 38% to 28% (25). Although post-release treatment rates did not increase, individuals with substance use disorders who received treatment were more likely to have their care paid for by Medicaid in 2014 compared with prior years.

Emergency departments are also an important point of intervention because increased fentanyl in the street drug supply translates into non-fatal fentanyl-involved overdose visits in the emergency room. Emergency departments offer a unique setting to rapidly initiate treatment and connect individuals to evidence-based services after discharge (26). Here again, improved insurance coverage under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion has made it easier to support the transition of an individual seen in an emergency department into evidence-based treatment in community-based treatment settings.

6. Stigma Reduction Messaging Emphasizing the Risks of Fentanyl

Research shows that public attitudes toward individuals who use prescription opioids and heroin are extremely negative (27,28). High levels of stigma have been identified not only in the general public, but they are also common in key groups tasked with responding to the opioid epidemic, including first responders, public safety officers, and frontline health professionals (29). Research has indicated that stigma shapes beliefs about the appropriate public policy responses to the epidemic (30). One recent study, for example, found that high social stigma toward individuals using opioids was associated with greater support for punitive responses to the epidemic, such as prosecution of women if there is evidence of narcotic use during pregnancy (31). Another study found that stigma and misunderstanding in correctional agencies about the effectiveness of evidence-based treatments for opioid use disorder were barriers to more widespread adoption of such treatments in criminal justice settings (32).

To encourage broader adoption of harm reduction practices, well-established communication methods could be adapted, implemented, and evaluated to foster improved distribution of non-stigmatizing information about opioid use among the general public, individuals using opioids, medical professionals, police officers, and others. Communications about the risks of fentanyl should be a component of health communication approaches, including factual information about fentanyl-related risks and the availability of harm reduction methods to minimize the risk of fentanyl overdose (e.g., drug-checking services). These risk communication strategies should include targeting online forums (e.g., Reddit) and other settings regularly accessed by individuals using opioids.

3 Conclusions

The opioid crisis in the United States appears to be rapidly evolving from a prescription opioid-driven phenomenon to one increasingly characterized by high rates of mortality from illicit fentanyl use and fentanyl-laced heroin. This changing dynamic requires new approaches with greater emphasis on harm reduction. Although harm reduction methods tend to garner lower public support compared with more mainstream medical interventions, research suggests that, if framed effectively, these approaches can be politically feasible. It is likely that adoption of newer policies and practices aimed at harm reduction will be needed before we begin to turn the corner on tackling the epidemic. To effectively address the opioid crisis, policymakers and others should consider implementing all six of the key strategies described in this paper.

Although harm reduction methods tend to garner lower public support compared with more mainstream medical interventions, research suggests that, if framed effectively, these approaches can be politically feasible.