1 Introduction

As state and federal policy makers respond to alarming increases in rates of mental health conditions among children and youths, many seek to move beyond reactive policies toward upstream approaches to help prevent or mitigate diagnosable conditions (1, 2). Home visiting offers a wholistic approach for new parents and their young children through health education, parenting support, and other services at home (3). Evidence of its benefits—from improvements in child health and development to decreased criminal justice involvement and substance use—has accumulated over decades across a growing number of models. Some models are associated with improved mental health outcomes, including reduced family stress and maternal depression, and improved access to mental health services (4, 5).

The federal government made its first significant commitment to home visiting in 2010 through the Maternal and Infant Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program. Yet despite increasing federal investments and positive outcomes for many families, home visiting reaches only a small fraction of families who might benefit. Requiring all states to cover home visiting as a benefit for pregnant women and newborns through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) would greatly expand its impact. As the nation’s largest single coverage source for children, Medicaid has unsurpassed reach to more than 40 million children and millions more pregnant women and parents annually (6), and it covers a large share of maternity care in the United States (7). Therefore, the program offers a natural financing vehicle to bolster early childhood development, more effectively promote the mental health of both mothers and children, and build upon the past 13 years of progress in expanding home visiting services. Medicaid support for home visiting should be a component of any policy strategy to address the nation’s mental health crisis.

2 What Is Home Visiting?

Home visiting can promote a child’s ability to grow and thrive well into adulthood by supporting families as they navigate the vulnerable period of early infancy and new parenthood. Supportive interventions provided in the earliest stages of parenthood and child development can build family resilience and lead to a range of beneficial outcomes.

Home visiting can promote a child’s ability to grow and thrive well into adulthood by supporting families as they navigate the vulnerable period of early infancy and new parenthood. Supportive interventions provided in the earliest stages of parenthood and child development can build family resilience and lead to a range of beneficial outcomes.

With public health roots, home visiting is not new, but the term can mean different things to different audiences. Home visiting most often refers to a wholistic two- generation approach employed by a range of different models offering various specific services (8) (select model descriptions are included in the table in supplement 1). The often-interdisciplinary strategy aims to support parents and children during pregnancy and the newborn year and may continue throughout a child’s early development before kindergarten.

Through a two-generation lens, models—directly or indirectly—strengthen the parent-child relationship that is foundational to a child’s development. Sometimes called “early relational health,” the complex interpersonal interactions between young children and parents, caregivers, and other adults in their lives have impacts on lifelong health and well-being. Strong parent-child relationships, in particular, influence early brain development of young children as they learn to explore the worlds around them (9).

Nurturing parent-child relationships can provide critical protective effects for children facing early trauma and toxic stress that can interfere with healthy child development. Such adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include sustained neglect, domestic violence, parental substance use disorders, parent incarceration or deployment, parent death or illness, discrimination, and other challenges exacerbated by the pressure of poverty. The more ACEs that children encounter, the higher their risk for general medical and mental health problems (e.g., heart disease, depression, and suicide risk)

as adults. ACEs are also linked to poorer educational and economic outcomes (10–17). One in 10 U.S. children has experienced three or more ACEs. The proportions of children who experience at least one ACE are higher among Black and Latino children (61% and 51%, respectively), compared with White (40%) and Asian (23%) children (18).

Although much of the nation’s maternal health crisis is focused necessarily on mortality rates, the mental health of the parent and child also begs attention. Perinatal depression affects as many as one in eight postpartum mothers, with rates even higher among low-income parents and parents of color (19). A large and growing body of research links maternal depression and anxiety with adverse child development

(20). Untreated perinatal mental health conditions, between pregnancy and the first 5 years of a child’s life, carry a societal burden of $14 billion in the United States (21).

Despite the clear relationship between parent behavioral health and child development, evidence-based interventions that promote family and child health are not widespread. Home visiting offers an important vehicle to address parent- child relational health, encompassing at least 25 evidenced- based or promising models. Although no two models are exactly alike, models share some elements.

A large and growing body of research links maternal depression and anxiety with adverse child development.

Home visiting services typically include some combination of the following:

- screenings or broader health assessments of the mother or child, using results to provide or connect families to additional services;

- parent education or coaching designed to promote a child’s social-emotional development;

- a connection point and sustained care coordination to link and refer to needed services, including mental health supports in response to screenings; and

- home-based treatment, such as dyadic or family therapy, that supports parent-child relationship building.

Home visitors range from nurses, social workers, and early childhood development specialists to model-trained paraprofessionals, such as peer coaches (22).

Home Visiting Works With Other Interventions to Reach Young Families

Home visiting can complement, reinforce, or build on— and should not be intended to supplant—existing health care services that Medicaid covers. Although services at home may be convenient for many families, others may prefer to access services in a health care or community setting. The cross-system nature of home visiting allows for additional touchpoints to reach families before children enter kindergarten. Coordination and treatment planning across systems can help accommodate each family’s preferred way to access services and mental health care: at home, in the community, or a combination of locations (23). Home visiting models may be distinct from other Medicaid- supported health services provided to children, pregnant women, and their families, but these models can help bolster the impact of such services. Examples of such health services are described here.

Perinatal Case Management and Prenatal Care Coordination

Perinatal case management is frequently offered to new mothers and funded by Medicaid provided through home visits in 30 states to increase access to prenatal care and connect mothers to services (24). Although such programs share some goals of home visiting, perinatal case management is not typically viewed as being the same as the home visiting models described in this article. States can broaden the reach of Medicaid perinatal case management to include home visiting models designated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Michigan, for example, redesigned its perinatal case management programs to create a more robust home visiting program known as the Maternal and Infant Health Program, which has been determined by HHS to meet criteria for an evidence-based model.

Well-Child Check-Ups

Pediatric check-ups are more frequent during the early months of life to check progress toward developmental milestones and identify possible delays (25).

A number of models, such as Healthy Families America and Nurse-Family Partnership, have demonstrated improved access to well-child visits or screenings

(26, 27). Home visiting programs can help strengthen and reinforce ties between families and primary care doctors to identify or reinforce family strengths and needs. Pediatric practices may refer families to home visiting models for additional tailored support.

Mental Health Treatment

Home visiting programs can include mental health treatment or can better link families to or raise their awareness of mental health treatment. Use of early childhood mental health care, for example, is inhibited by lack of widespread understanding and consistent financing (28). Some home visiting models directly provide or embed mental health treatment within a home visiting program. Child First, for example, incorporates child-parent psychotherapy and is available for use in a variety of settings (29). Maternal mental health interventions include models such as Moving Beyond Depression (30–32), Mothers and Babies (33), and Reach Out, Stay Strong, Essentials for mothers of newborns, which is designed to address maternal depression within a home visiting program or in combination with the program (34). (Other dyadic mental health treatment interventions and their impacts are described in the table in supplement 1 [35–37]).

3 How Can Home Visiting Support Maternal and Child Mental Health?

Home visiting provides a two-generation approach to promote early relational health. Specific goals and services vary by model, but short- and long-term benefits of home visiting have emerged across many domains. Better health, positive parenting practices, and other demonstrated effects can affect caregiver and child mental health, laying a strong foundation for long-term success (38). Some models show evidence of increased mental health screening, connections to needed treatment, or improved parenting practices that support child’s positive social-emotional development. (As described in supplement 1, participation in Child First, Early Head Start Home-Based Option, Family Spirit, Healthy Families America, and Nurse-Family Partnership can lead to improvements in at least one behavioral health outcome for mothers and children [4, 5]).

Better health, positive parenting practices, and other demonstrated effects can affect caregiver and child mental health, laying a strong foundation for long-term success.

4 Funding for Home Visiting

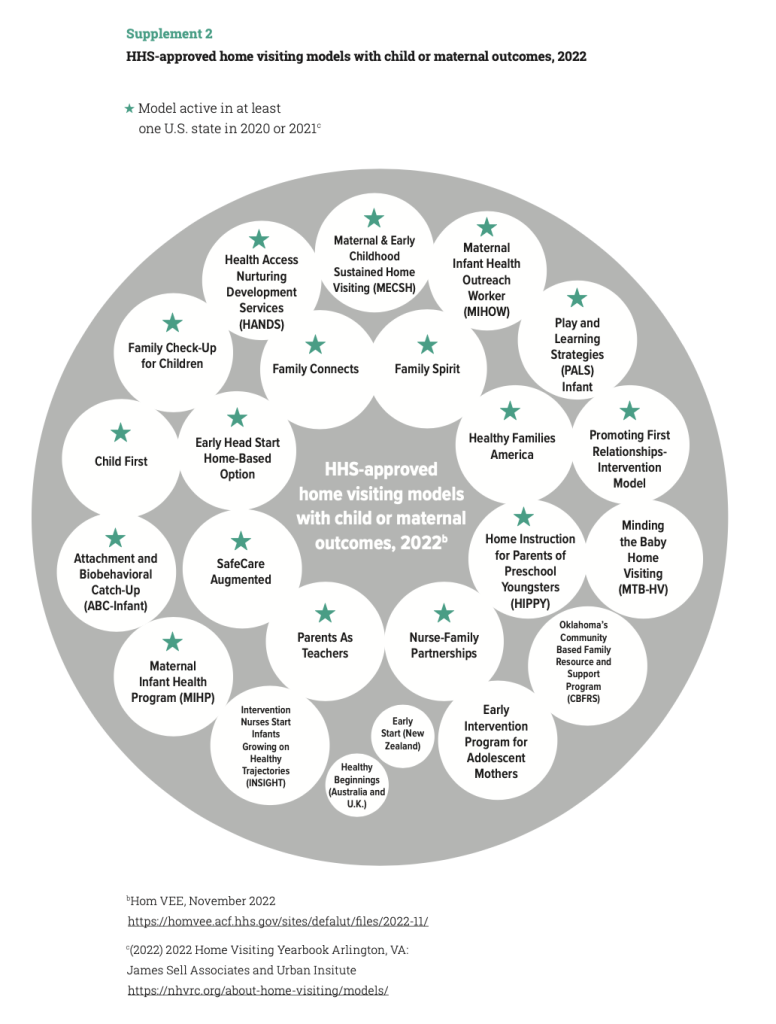

States pay for home visiting through a range of federal, state, and local funding sources. At the federal level, the primary funding source is MIECHV, a grant program that has awarded $400 million each year to states to pay for evidence- based programs and that Congress recently reauthorized through 2027 with substantially boosted funding (39, 40). Under MIECHV, HHS conducts systematic, comprehensive evidence reviews of home visiting models. The HHS-sponsored Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE) review assesses research on each model to ensure evidence meets eligibility criteria for most MIECHV funding (41). Currently, MIECHV supports 20 HomVEE-approved models and emerging models in all 50 states, as well as territories and tribal-led organizations (42) (see supplement 2 for a diagram of 2022 approved models and a detailed table listing a subset of select models and their outcomes). MIECHV also allows a portion of funds to support promising home visiting approaches as a more robust evidence base is secured. This approach offers an important strategy to continue to develop community-driven models to address cultural and linguistic needs of underrepresented families of color and to add to the research base strategies that are centered on the unique experiences of diverse populations. Many states use several funding sources, including federal and state grant programs from child welfare (Title IV-E and Title IV-B of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act), human services (Temporary Assistance to Needy Families), mental health (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration grants), and public health (Title V of the Maternal and Child Health Block Grant) agencies (43).

5 Scaling Home Visiting: Medicaid’s Role and Untapped Potential

Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of home visiting models and the dedicated federal funding through MIECHV, only approximately 300,000

families received home visiting from evidence-based or emerging models in 2021, reaching less than 4% of the children and families who might benefit (42). Additional MIECHV funding will further increase the numbers of families served, but closing the gap between need and available capacity requires sustainable, ongoing financing through policy changes that realize Medicaid’s untapped potential (44). More than 85% of children served by MIECHV programs in 2021 were covered by public insurance (42).

Medicaid provides health and long-term care coverage for low-income individuals in the United States, accounting for one out of every six dollars

that the nation spends on health care (45). As of June 2022, together with its companion program CHIP, Medicaid covered more than 85 million people, including more than 40 million children (46). In 2020, 12.7 million children under age 6 were covered by Medicaid, including more than 2 million infants in their first year of life—a critical opportunity to reach many mother-baby pairs (47).

Medicaid’s reach to underserved communities also makes the program an important player in advancing equity in maternal and infant health. Medicaid pays for more than 40% of all U.S. births, including 65% of births to Black women and 60% of births to Hispanic women in 2019 (48, 49). More than half of Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native children in the United States are covered by Medicaid or CHIP (50).

The federal and state governments, which together fund and administer Medicaid, spent more than $630 billion on the program in 2019 (51). The federal government provides most of the funding, matching state spending at a rate that varies by state and by some services. Federal dollars pay for at least half the cost of direct services provided to individual beneficiaries (45). Medicaid’s financing structure offers the possibility for more reliable and consistent funding for qualified home visiting programs, with capacity to follow billing processes for reimbursement. Congress does not have to act to renew or extend federal Medicaid funds. In contrast, other federal programs, including MIECHV, rely on congressional action to renew funding through the appropriations process.

Medicaid’s financing structure offers the possibility for more reliable and consistent funding for qualified home visiting programs, with capacity to follow billing processes for reimbursement.

The federal government, through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) within HHS, administers and oversees Medicaid. States and territories make policy decisions regarding eligibility, benefits, delivery systems, and other areas within federal standards and above federal minimums.

Medicaid’s Current Coverage of Home Visiting

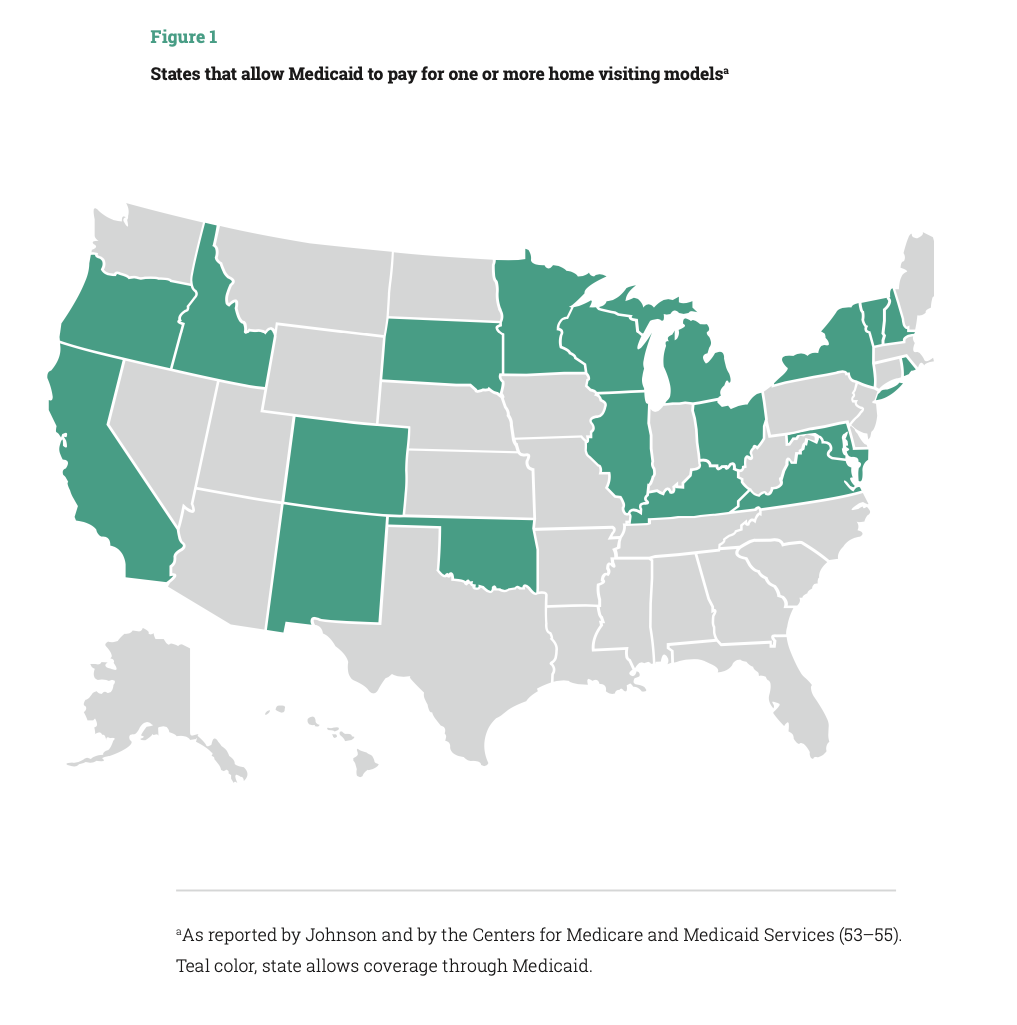

Although some states have been covering home visiting services through Medicaid for decades, attention to Medicaid’s untapped potential has grown. In 2016, CMS and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) provided guidance encouraging states to expand home visiting and clarifying ways in which states could use Medicaid (52). Twenty-one states now cover home visiting models through Medicaid for eligible pregnant women, children, or parents (Figure 1) (53–55). Yet even in states that fund home visiting in Medicaid, services may not be available statewide or to all populations that need them. The National Home Visiting Resource Center estimates that an additional 18 million pregnant women and families with children under age 6 could benefit from home visiting, based on one of five prioritization criteria: caring for an infant, income below the federal poverty line, pregnant or parenting mothers under age 21, single or never married parents or pregnant women, and parents with less than a high school diploma (42). Across states, home visiting programs reach between 0.1% (Vermont) to more than 9% (Michigan) of potential families (42).

There is no specific home visiting benefit in Medicaid. Instead, states can choose from different authorities to cover many services included in home visiting programs (such as screenings, case management, family supports, and specific treatments, such as dyadic or family therapy). Most states cover home visiting through Medicaid’s Targeted Case Management benefit, which aids beneficiaries in accessing medical, social, educational, and other services and allows states to target services to specific populations and geographical areas (56). States also use Medicaid’s comprehensive benefit for children, Early Periodic Screening Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT), pregnancy-related services for women, and section 1115 demonstration waivers to cover home visiting (52).

More state Medicaid agencies have also begun to allow for reimbursement of doulas for pregnant beneficiaries.

To qualify for reimbursement, home visitors must meet Medicaid provider criteria set by the state (52). Many providers are nurses and social workers, but more states are creating programs to reimburse community health workers, doulas, and peer mentors who may be employed by home visiting models based on each model’s staff qualifications (57). Minnesota, for example, allows community health workers to serve as home visitors (43). Use of community health workers as home visitors can help reflect the cultural and linguistic make-up of communities served, an important strategy for promoting health equity, especially among Black and Brown families, who have been historically underserved (58). More state Medicaid agencies have also begun to allow for reimbursement of doulas for pregnant beneficiaries (59, 60). Home visiting models, such as Parents as Teachers, may employ doulas as part of the service team (61, 62).

A new state Medicaid option to extend postpartum coverage offers an important platform for home visiting services for new parents and their newborns. The 2021 American Rescue Plan Act gave states an option to extend coverage to pregnant women in Medicaid and CHIP from 60 days to 12 months postpartum. More than 35 states and the District of Columbia have implemented or moved to adopt this extended coverage period, with additional states likely to adopt it in the coming months and years (63). States can use the opportunity of establishing the extended full year of coverage to provide home visiting benefits to many more new mothers and their newborns (64). This can help advance maternal mental health and newborn screenings and connections to services, a goal that CMS established in its implementation guidance (65). New Mexico, for example, is seeking to expand access to home visiting in Medicaid by making new models available to postpartum mothers and their children. The state submitted a waiver application and is awaiting federal approval to add four evidence-based home visiting models to an existing pilot program, making new expanded services available during and beyond the postpartum period (66). The range of available models will help the state deploy multiple approaches to address a variety of unique family circumstances and help create a continuum of home-based services.

Expanding home visiting services through Medicaid can help connect families to other follow-up prevention and intervention services that they might need, including mental health and other follow-up services that Medicaid covers. Home visiting can also help Medicaid meet its obligation to ensure preventive screenings and needed care to children, which are required under Medicaid’s pediatric benefit EPSDT (67, 68).

Scaling home visiting through Medicaid presents a clear opportunity to better align health and mental health in the postpartum period, complementing state policy initiatives to address high rates of maternal and infant mortality. Too often, mental health has not been a central focus of efforts to serve new parents and infants, despite its clear relationship to maternal and child health.

Home visiting can also help Medicaid meet its obligation to ensure preventive screenings and needed care to children, which are required under Medicaid’s pediatric benefit Early Periodic Screening Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT).

Finally, stronger Medicaid coverage policies would ensure a substantial, ongoing source of financing for home visiting. Leveraging Medicaid can help stretch limited public or private grants further, redirecting grant funding to develop new capacity or to pay for costs Medicaid does not reimburse. Having more comprehensive, stable financing, along with expanding the reach of home visiting, could create new incentives to build state and local home visiting capacity, which despite recent growth remains limited.

Additional Federal Actions to Accelerate Medicaid Financing for Home Visiting

The need and growing urgency to promote the mental health of mothers and children warrants strong federal leadership to expand home visiting through Medicaid. Federal policy makers can use a combination of legislative and administrative actions, which are described below.

Make evidence-based home visiting programs a required state benefit during pregnancy and through the child’s first year of life.

To expand and scale home visiting services, Congress should require states to cover Medicaid home visiting. For the first 5 years, this benefit would be optional in order to allow states to adopt new models and build home visiting capacity. At the end of that 5-year phase-in period, home visiting would become a required Medicaid benefit in all states. The mandatory benefit would apply to pregnant women and their children through the first year of an infant’s life and would be available statewide. Congress should also give states flexibility to extend the benefit for families with children ages 1 through 5. Congress should also provide grants to states to develop the capacity of home visiting providers, including strengthened or streamlined ability to effectively enroll in and bill for Medicaid reimbursement.

The new benefit would give states the ability to choose one or more HHS-reviewed models, along with a state option to include additional promising research-based models with emerging evidence. Congress should task the HHS HRSA, which operates HomVEE, with reviewing models that include or pair with specific mental health interventions, such as Moving Beyond Depression or Child First. States could choose from and deploy a variety of HomVEE-reviewed models to meet the new mandatory requirement, targeting different models to specific populations or geographic areas.

In 2020, Medicaid covered more than 2 million newborns in their first year of life and more than 10.5 million young children ages 2 to 6 years (46). Making home visiting a Medicaid benefit would bring services to far more families, offering additional chances to access needed mental health services during a time of rapid change for the family. It would also complement Medicaid postpartum coverage extensions to 12 months, making the most effective use of the longer coverage period. The cost to the federal government of establishing this new mandatory benefit could be modest, because evidence suggests that some home visiting models are highly cost- effective and have benefits that exceed their costs (69).

Clarify how states can effectively coordinate federal funding streams that support home visiting.

States seek to build more seamless and coordinated service delivery by maximizing use of MIECHV, Medicaid, and other federal and state funds. But lack of clarity on federal rules can inhibit the development of successful financing and service approaches. For example, federal law requires that Medicaid serve as the payer of last resort to ensure other available insurance sources pay before public safety-net dollars are spent. Congress has made exceptions to this rule in the case of some federal programs with more limited financing that provide direct services to children and families, such as the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act Part C Early Intervention, Families First Title IV-E prevention services, and Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant (70). Congress should make a similar clarification exception with MIECHV to minimize implementation confusion when states seek to use funding sources together.

Proactively identify strategies to maximize the reach of Medicaid with other federal programs for in- home parent and early childhood mental health services.

Require HHS to provide technical assistance to states on ways to advance home visiting.

Federal agencies, specifically CMS, HRSA, and the Administration for Children and Families, should support state efforts to take up home visiting and support state integration of home visiting across child-serving systems. Technical assistance can help states consider the best ways to help community-based organizations outside the traditional health system to bill Medicaid more effectively and to clarify mechanisms to use Medicaid alongside other federal funding. Congress should assign HHS this responsibility and provide additional funding for technical assistance.

Proactively identify strategies to maximize the reach of Medicaid with other federal programs for in-home parent and early childhood mental health services.

Some evidence-based prevention and treatment interventions that may be provided in the home (see table in supplement 1) may not be considered “home visiting” programs on the basis of HHS criteria but may qualify as eligible treatment services under Medicaid. HHS should coordinate across programs and funding sources to advance high-impact strategies for states to use Medicaid most effectively, along with other federal funding sources.

6 Conclusion

Expanding home visiting through Medicaid has the potential to help achieve better outcomes for maternal health, child health, and mental health—all national priorities. Home visiting has been shown to have positive impacts on outcomes of mothers and children that extend well beyond a child’s first years of life. Home visiting can offer an effective approach to meet families where they are, support new parents and newborns at a critical stage in life, and strengthen their resilience over time. As the largest single source of coverage for young low-income children and their families, Medicaid should do more to advance home visiting to reach more families who could benefit. As federal and state policy makers seek to address maternal and child mental health, they should adopt an assertive strategy to expand the reach of home visiting services through Medicaid.